Finally alone after eleven hours of feverish demands, threats and hostage exchanges, the hijacker pulled off his shaggy brown wig and began to disrobe. He shrugged out of a burgundy sport coat, white dress shirt and yellow trousers — it was, after all, 1972 — revealing a second outfit: a set of dark-colored slacks and a collared blue t-shirt. Upon surveying the rows of empty seats running the length of the Boeing 727, he checked his wristwatch. Only a few hours remained until sunrise.

It was after 3 a.m. on June 24, and the purloined aircraft was hurtling through a cloudy night sky, heading for the Canadian border.

The hijacker, Martin McNally, was 28 years old, but with his boyish face and near-smirk, could pass for a teenager. He scooped up the discarded clothing and walked to the very rear of the plane, arriving at the open hatch and extended stairwell. He stared into the murky darkness below.

There was still time to call it off, McNally thought. He could turn around, walk back to the cockpit and hand his rifle to the pilot. He could return the bag stuffed with $500,000 cash and then, somehow, talk his way out of the mess he’d left back in St. Louis. He could tell the FBI agents that there was never any bomb on the plane, that it was all joke.

McNally tossed the wig through the hatch, followed by the clothing, several smoke bombs and the rifle with its two loaded cartridges. The items whipped into the air and disappeared. This was no time for second thoughts.

Aside from a single hostage, McNally was now the only non-crew member left on the flight. Hours before, on the tarmac at Lambert International Airport, he’d negotiated to release more than 90 passengers in exchange for a fresh crew to fly him to Toronto — a city McNally had no intention of visiting. Soon after takeoff, he’d ordered the sole remaining American Airlines stewardess (through whom he had relayed all of his demands) to join the hostage and flight crew in the cockpit.

Now, McNally’s only companion was the thrilling weight of a cash-heavy mailbag tied to his left belt loop.

After strapping on a pair of flight goggles, McNally donned a reserve parachute, tightening the straps around his legs and chest, just as he’d been instructed by an FBI agent during an on-the-spot lesson earlier that evening. McNally had never touched a parachute before. This would be his first jump.

Slipping a handgun into his pocket, he descended the stairs haltingly, on his butt, scooting down step-by-step into the roar of the wind. He turned onto his stomach, catching one last look at the rear hatch leading into the passenger cabin; he imagined how easy it would be for someone on the plane to walk back here and shoot him in the head.

McNally’s hands were the only things keeping him connected to the plane. His body, suspended from the stairwell at 300 miles per hour, felt like a daisy caught in a hurricane.

In the cockpit, the remaining crew felt their ears pop as the cabin pressure fluctuated.

One thousand feet above the Boeing 727, from the vantage point of a military surveillance plane, an FBI agent observed a small, dark object falling rapidly from the rear hatch.

McNally dropped like a bullet, feet-first, and the first thing he perceived was the wind punching his flight goggles into his eye sockets. In seconds, the goggles were violently ripped from his head. McNally threw out his arms, bringing his body parallel to the ground as he began counting down from twenty in his mind. Basing his calculations on the formula for terminal velocity — which he’d learned in a library physics textbook — McNally figured that this would be enough time to slow his fall to a safe speed. If he pulled the chute too early, he knew, the air would shred the canopy like tissue paper.

The time came to test his math. McNally fumbled for the ripcord with his right hand, but he made the mistake of leaving his left arm outstretched. Instead of producing the serene, deliberate movements of an experienced skydiver, the wind took hold of his arm and slammed the hijacker into a furious spin.

In the midst of the chaos, the parachute exploded out of the chest harness and ejected its spring-loaded contents directly into McNally’s face. Blinded and hurting, he managed to grab hold of the shroud lines above him. He tugged hard, and was rewarded with resistance as the canopy filled with air.

McNally was going to live after all. His hand strayed down to his left thigh, hoping to be reassured by its half-million dollars.

He could only look down in horror. The mailbag was twenty feet below him, and getting smaller and smaller by the second. As if in a dream, McNally watched the fortune tumble in slow-motion, end-over-end, until it slipped below the clouds and vanished.

The hijacker considered his options.

Forty-four years later, on a sweltering afternoon in August 2016, Martin McNally enters the Thomas Eagleton U.S. Courthouse in downtown St. Louis. He rides an elevator to the second floor and checks in at the front desk of the federal probation office.

Clean-shaven, his white hair combed and slicked back from his forehead, the 72-year-old ex-con is anticipating good things from a scheduled meeting with a federal parole supervisor. Five years out of prison, McNally is now permitted to apply for release from his permanent parole, a status that saddles him with travel restrictions and random checkups. The meeting could set the wheels of true freedom in motion.

By the time McNally had been released from a California prison in 2010, he had already spent more than half his life behind bars. He then settled into an apartment in south St. Louis, where he subsisted on disability benefits linked to an old Navy injury.

McNally’s first decade as inmate had been marked by violence and multiple failed escapes. He was involved in numerous scraps with prisoners, and, although never convicted, he was twice brought up on charges for assaulting guards in the U.S. Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas. In one instance, he was accused of wielding two sharpened pencils as shanks.

“My first ten years, those were turbulent, no question,” McNally says, making conversation in the parole office waiting room. “The guards at the U.S. Penitentiary in Leavenworth were brutal. They beat up and assaulted prisoners; they killed prisoners. So yes, there were assaults on guards, there were indictments.”

By the early 1980s, the inmate had calmed down a good deal. McNally dedicated much of the next three decades to appealing his conviction for air piracy. He became a proficient jailhouse lawyer, ran for president and accrued more than $10,000 by illicitly trading Wall Street stocks.

At the courthouse, McNally waits an hour before he and his local parole officer are beckoned into the conference room to meet the supervisor.

The meeting lasts under 30 minutes, and it doesn’t look good. During the meeting, the local officer testifies that it would be best to keep the septuagenarian hijacker on parole indefinitely.

On the drive back to his apartment, McNally unleashes a stream of curses, mostly directed at the parole officer.

“I would recommend retaining him on parole,” McNally quotes, sneering his impression of the testimony, “because of the nature of this crime.”

Fuming, he says, “Yeah, no question, I’ll be on parole until I’m dead.”

NATIONAL ARCHIVES AT KANSAS CITY

Beginning in the mid-1960s, the“Golden Age” of airline hijacking was an era when any passenger could walk through an airport terminal unmolested, breeze onto the tarmac and board a plane — all that with their shoes on, no less. In some cases, you could even pay for your ticket on board.

This casual freedom — a relic of a more civilized time — persisted in the face of an unprecedented wave of hijackings. Early interventions proved laughably inadequate, flabbergasting airline companies. Ticket agents were instructed to subjectively screen passengers based on a cooked-up checklist of psychological and physical traits believed to be particular to hijackers, and although sky marshals were deployed in 1970, their limited ranks couldn’t hope to make a dent in the vast number of flights taking off each day in American airports.

The virtually non-existent security led to a frenzy of hijackings. According to Brendan Koerner’s 2013 book chronicling the period, The Skies Belong to Us, more than 130 hijackings were committed in American skies between 1968 and 1972.

Many of the culprits were straight nutjobs, driven by religious or political yearnings that required (for some reason or another) immediate passage to Cuba. But even as the capers escalated in audacity and potential violence, airlines companies balked at beefing up their own security. Instead, they sought to avoid the possibility of violence at all cost. Crews were instructed to comply with hijackers’ demands rather than risk an altercation. Pilots on domestic flights were provided with charts outlining passage to Havana, just in case.

But there was a second, altogether different species of hijacker: not a nutjob, but rather a certain kind of foolhardy opportunist. In other words, a common crook.

Driving through Detroit in January 1972, Martin McNally listened with growing interest to a radio news report of a two-month-old hijacking in the Pacific Northwest. Shortly before Thanksgiving, an unidentified man had commandeered a Boeing 727 after taking off from Portland International Airport.

According to the report, the hijacker had ordered the plane to land and subsequently demanded a parachute and $200,000. Upon receipt, the hostages were released, but the hijacker kept the crew and ordered the plane to take off once again. Forty-five minutes into flight, the man jumped from the lowered stairwell at the rear of plane. Both hijacker and cash had seemingly disappeared without a trace.

In the coming months, McNally would spend hours poring through library books on parachutes and skydiving. An idea took root in his mind. The hijacker on the radio — soon mythologized as “D.B. Cooper” — had demonstrated an effective strategy for air piracy, and it seemed a much easier task than knocking over an armored truck or a bank.

McNally was a product of a large family, and had lived most of his life in his hometown of Wyandotte, a suburb in the southern shadow of Detroit. McNally’s father, a shoe store owner and respected figure about town, had put eight children through Catholic school. But young Marty McNally spurned his studies. Instead of completing eleventh grade, he enlisted in the Navy, where he labored as an airplane electrician. It was no harbinger of destiny: His flight time was restricted to servicing the cramped patrol craft sweeping for Soviet submarines off the coast of Alaska.

Given a general discharge from the Navy in 1964, McNally had no interest in joining his father at the family shoe store. He wound up scrambling through a series of odd jobs and minor scams, including a plan to embezzle gas sales from a service station and a short-lived counterfeiting operation, which ended when he was busted feeding fake quarters to a laundromat change-machine. By 1972, he was exhausted with the paltry returns on minor scams.

One big score, that’s what he needed. All he required was a weapon, some phony documents and a passable disguise. D.B. Cooper had shown him the rest.

Getting the gun was easy. A local pool hall hustler, Walter Petlikowski, provided a .45 rifle, and McNally cut ten inches off the barrel. The weapon fit comfortably inside a black attaché case with a wig and smoke bombs. Petlikowski, in turn, signed on as an accomplice in exchange for $50,000.

In the fall and winter of 1972, McNally charted a tour of Midwest cities, hitting Indianapolis, Chicago, St. Louis and Kansas City. He settled on St. Louis’ Lambert Airport — it had the worst security, McNally says — and made two more trips to the airport with Petlikowski to prepare for the one-way flight.

On the morning of June 23, a Friday, Petlikowski dropped McNally at the main terminal. Petlikowski had changed his mind about participating in the hijacking directly, but he’d still agreed to act as chauffeur for half his original fee. McNally, briefcase in hand, bid his accomplice farewell and boarded Flight 119 destined for Tulsa, Oklahoma.

McNally encountered no metal detectors on his way to the flight. His ticket, purchased with forged Navy discharge papers, identified him as “Robert Wilson.”

Less than 30 minutes before landing in Tulsa, McNally excused himself from his seat three rows from the rear of the plane and walked to the lavatory. When he emerged, he was wearing a shaggy brown wig and sunglasses and wielding a rifle. He handed a note to a startled stewardess.

A few minutes later, the captain’s voice came over the intercom:

“Ladies and gentleman. We have a passenger who needs to return to St. Louis.”

McNally followed D.B. Cooper’s example to the letter, though he added a key embellishment: McNally demanded more than twice Cooper’s ransom, asking for $500,000. He also requested another $2,000 in small bills, most of which he gifted to the stewardesses as a tip for their compliance.

Around 4 p.m., Flight 119 returned to St. Louis and came to a stop on a runway on the far edge of the airfield. McNally made his demands known. He claimed to control the detonator to a bomb somewhere on the plane, and that any attempts at resistance would be met with gunfire.

Over the next hour, a flurry of negotiations and counter-negotiations played out between the hijacker — who relayed all messages to the cockpit via stewardesses — and FBI agents on the scene. Eventually, McNally permitted 80 hostages to leave the plane by way of the plane’s inflatable emergency slide.

But raising a half-million dollars on a Friday evening was no easy task. It could take hours. So, after refueling, McNally directed Flight 119’s crew and the fourteen remaining hostages to ready themselves for takeoff. Back in the air, the plane traced circles above St. Louis. At one point, McNally allowed the pilot to redirect the plane to Fort Worth, Texas, based on reports that the money could be collected there much faster. That report turned out to be premature, and the plane instead turned back to St. Louis, where bank and airline officials were still scrambling to put together the ransom.

It was after 9 p.m. when their efforts succeeded. Flight 119 made its second landing on a Lambert runway. Now, McNally relayed three additional demands: He needed a shovel, flight goggles, five parachutes and two harnesses.

The money was delivered in two packages: a heavy airmail bag and a small wrapped parcel. However, despite his preparations, McNally struggled to figure out how to buckle the parachute harness. So he added an additional request: for someone to show him how to put the thing on.

When the “instructor” (actually an undercover FBI agent) came aboard, McNally watched from a distance of several feet, rifle at the ready in case of ambush. The instructor/FBI agent made no move to disarm McNally, and after his quick lesson, left the aircraft unharmed.

It was just after midnight, and the plan seemed to be chugging along perfectly. McNally released thirteen more hostages, leaving under his control one hostage, two stewardesses and the flight crew.

TV and radio stations were already broadcasting the unfolding drama across the country. From behind the rectangular glass facade of the main Lambert terminal, throngs of passengers watched as a tanker truck refueled Flight 119, readying the plane for its fourth St. Louis takeoff in the past eight hours.

But nothing could have prepared McNally for the interference of a young Florissant businessman, David Hanley, who was among the bystanders ogling the drama from the terminal.

Hanley did not remain a bystander for long. As the jet taxied down the runway, its massive engines revving in preparation for takeoff, Hanley’s 1971 Cadillac Eldorado crashed through the runway’s perimeter, battering through a fence at 80 miles per hour on a collision course with Flight 119.

The plane, heavy with fuel, was essentially a bomb with wings. Over the intercom, the captain’s voice crackled with panic. “Oh my god, there’s a vehicle on the runway!”

Hanley steered the Cadillac into the nose of the plane. Inside, the impact knocked McNally forward in his seat, and the heavy vehicle careened through the nosewheel, coming to a smoldering halt against the landing gear beneath the portside wing. The damage was superficial — the jet fuel did not ignite — but the plane was crippled.

(Interviewed by the Associated Press one year later, Hanley claimed that the crash had wiped all memory of that night, and that he was as mystified by his actions as everybody else: “My mind is a blank from 6 o’clock that night to two weeks later.” As for “reports” that he’d left a cocktail lounge near the airport, telling friends he “would shock the world,” Hanley denied it. “If I was there then any friends who were with me were a bunch of slucks,” he told the AP. “No one has come to me and said, ‘David, I was with you that night and this is what you said.'”)

An ambulance arrived to take Hanley to a hospital. He’d suffered two broken jaws, broken ribs, a fractured skull and a crushed left arm and ankle — but the only damage McNally cared about had been inflicted on his getaway ride. The aircraft was useless now. McNally relayed an urgent message to the cockpit: “Get me another plane.”

It took 90 minutes to bring a second Boeing 727 alongside the disabled airliner. Fearful of FBI snipers, McNally pressed himself between two stewardesses and covered his head with his briefcase until he safely entered the new plane’s lowered rear stairs.

The second plane was fueled and ready for takeoff. Along with his civilian hostage, McNally presided over the jet’s three-man replacement crew as well as the one remaining stewardesses he’d kept from Flight 119. There was no need for more leverage than that. McNally ordered the plane to leave St. Louis and set a course to Toronto.

Tracing a straight line, the flight path would take the plane over the vicinity of Detroit. In the preceding months, McNally had tried to work out the precise timing of his jump based on the plane’s airspeed, but he now worried that the delays had disrupted his calculations. He had originally planned to make his jump shortly after midnight. It was now nearly 4 a.m.

Still, it was time to leave. He stripped off his disguise and buckled the parachute’s harness around his arms and legs.

McNally didn’t know where he was. From 10,000 feet, the undisturbed whiteness of the clouds below had obliterated any landmark or geographic feature. He wondered if the pilot had betrayed him, and whether he was seeing not clouds but the deep waters of Lake Michigan.

In reality, McNally chose to make his jump too early. The plane was passing above central Indiana, about 150 miles southwest of Detroit.

Having already hijacked two planes that day, getting to the ground should have been the easy part of McNally’s plan. He intended to bury the money immediately, leave the area and lay low for a few weeks or months. Then he would return with a shovel.

McNally dropped from the rear stairwell. Without firing a shot, he’d just made more money than he’d ever earn in a lifetime of shoe sales or petty crime.

But riches were not in McNally’s future. Gravity saw to that.

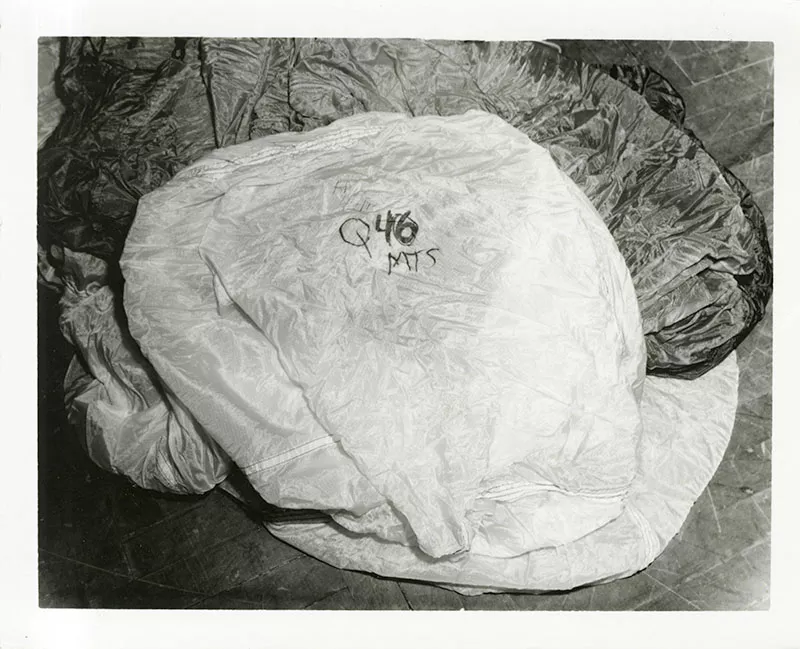

NATIONAL ARCHIVES AT KANSAS CITY

McNally landed hard in a barren field, narrowly missing a grove of trees. He had made a mistake, panicked on approach, thrusting his heels into the soil and causing his body to whip backwards into the ground. His head bounced on the soil, leaving him concussed. His vision danced with stars that were not really there.

The money was gone. It had disappeared, eaten by a blanket of clouds in a moment that imprinted itself in McNally’s mind like a nightmare. There was nothing he could do. He didn’t even know where he was; the lack of discernible landmarks on the ground made triangulation useless. Of the $502,000 he’d had in his hands, all he had now was $300 that he’d pocketed before the jump.

McNally peeled himself off the ground. Around him, the sound of dogs barking echoed through the night. He gathered the parachute and clambered over a barbed wire fence surrounding a thicket of trees. Finding a suitably covered spot, he laid out the parachute and collapsed for two hours.

At dawn, woozy and shivering, he dragged the chute deeper into the woods, where he covered the canvas with leaves and shrubs. He climbed into the parachute’s folds as if it was a cocoon and slept until noon.

McNally awoke to helicopter blades thumping overhead. The search parties were already on the move, hoping to sniff out the skyjacker and the loot.

He decided to wait for dusk before moving from the forest’s tall canopy. In the meantime, he napped, buried the parachute and cleaned his clothes and shoes as best he could.

Again crossing the barbed-wire fence, McNally walked 500 feet before coming to a gravel two-lane road. In one direction, he perceived a white glow against on the horizon, possibly a city or town. He began trudging in that direction, the monotony broken only by a few cars with Indiana license plates passing by.

An hour and a half later, one car stopped short about a quarter-mile down the road. In the driver’s seat was Richard Blair, the police chief of Peru, Indiana. Chief Blair had been driving back to Peru with his wife, and the sight of a lone pedestrian on the road so late at night tugged his interest.

McNally introduced himself as Patrick McNally (his older brother’s name) and displayed a Michigan driver’s license (a forgery) that corroborated the ID. Though McNally’s two credit cards were issued to a “J. McNally,” he explained to the chief that he had borrowed the cards — with permission — from his brother.

The chief asked McNally what he was doing out on a country road after 9 p.m.

McNally claimed he had recently traveled to Peru from Detroit on a mission to retrieve his brother from a nearby farm. Alas, McNally continued, his brother had gotten drunk earlier that night and beaten the snot out of him, leaving McNally in this sorry state.

McNally’s eyes and cheeks were heavily bruised, his chin was gashed open and he sported several cuts on his forehead. He really did look like he’d taken a beating. Chief Blair offered a lift to Peru, and McNally gladly took him up on it.

Before climbing into the car, McNally quickly slid the handgun from his pocket and tossed it to the side of the road.

(“He did not frisk me,” McNally would later recall. “If the chief had said anything about patting me down, I would have pulled out this pistol from my right pocket, cocked it and said, ‘You’ll search nothing.’ He and his wife would probably have been killed at that point.”)

On the drive to town, Blair warned McNally that it was a bad time to be alone on the road, what with so much traffic speeding back and forth. Hadn’t he seen the news? Search parties were scouring the area for a hijacker and a bag of money. McNally answered vaguely in the affirmative, and thanked the chief for saving him the long walk and potential hassle. Blair dropped McNally off at the Peru Motor Lodge, across the street from police headquarters.

It was late, and McNally hadn’t tasted food in more than 24 hours. He also hadn’t had a chance to look in a mirror. Sitting down for a burger in a nearby bar, he felt the eyes of the other patrons evaluating him from all angles. He wasn’t losing his mind to paranoia. In the bar’s bathroom, McNally stared in shock at his bruised and puffy reflection. No wonder he was getting weird looks.

McNally returned to the motor lodge and bought a room for the night. The elderly desk clerk accepted his explanation about the mismatched driver’s license and credit cards, but she couldn’t help but notice the condition of his face.

“You aren’t that skyjacker, are you?” she asked.