This story was commissioned by the River City Journalism Fund

Ta’janette Sconyers, a psychologist hired to work with youth at the St. Louis Juvenile Detention Center, found herself grappling with her own anxiety and despair over conditions inside the facility. It got so bad that she took a leave to protect her mental health.

Finally, in 2019, she simply resigned, becoming part of the turnover at the detention center, which seemed to do so little to provide youth with treatment, rehabilitation or even sunshine and fresh air.

“They said it was a revolving door. But I always asked, did anyone ever take the time to figure out why the door kept revolving,” says Sconyers.

Sconyers specializes in treating the effects of anxiety, trauma and OCD, and those were also some of the issues she diagnosed and treated while working at the St. Louis Juvenile Detention Center on Enright Avenue. It’s one of 18 juvenile detention centers in Missouri operated by the circuit courts that hold minors accused of crimes and deemed threats to public safety. Administrators say rehabilitation and treatment are the goals for the approximately 2,000 youth in the state who funnel in and out of the detention centers annually.

If a youth is found guilty of a crime, the courts can commit them to a more permanent secure facility operated by the state’s Division of Youth Services, which has about 20 residential facilities and housed more than 1,200 youth last year. Youth can also end up at state facilities if they are repeatedly caught committing crimes. While legal terminology refrains from referring to these institutions as youth jails and prisons, they are still forms of incarceration, Sconyers points out.

Many of the youth never spoke to her, although some would check to make sure she was around every day. Others would open up to her about why they made the decision they did — money and a dissociation from their actions, she says.

But Sconyers ultimately concluded that her attempts to make a difference were futile.

“I felt I had more of a chance of helping them by not being a part of the system,” says Sconyers, who resigned from the facility in 2019 and is now in private practice. “If people’s basic needs aren’t being met, how do you think I’m going to be able to sufficiently address their trauma?”

A series of escapes in recent years has changed the policies at St. Louis area detention centers. It’s one reason why St. Louis area facilities, most which have outside recreational areas, have stopped allowing detained youth to use them. Amanda Sodomka, who led the city’s juvenile detention center as chief juvenile officer for the 22nd Circuit Court until a recent promotion, says the city’s juvenile facility is working on upgrades to the doors and a higher fence in order to consider allowing youth outside again.

“We have very smart youth,” says Sodomka. “It poses enough risk, we just can’t have them outside right now.”

Yet Sconyers says the lack of fresh air was one of many things that disturbed her. Some youth were only there for days, but others for months or years as their cases played out. She and other staffers attempted multiple times to organize letting youth go out for even a few minutes each day, but those efforts were always shot down.

And that was even before her facility saw an unprecedented number of escapes, as did many other St. Louis area detention facilities. Juvenile administrators and staff point to the recent “Raise the Age” state law that requires 17-year-olds not to be tried as adults, which went into effect in 2021. Data from the Missouri Supreme Court confirms most of the escapes from the juvenile detention facilities were from youth just a year shy of being legal adults.

News reports about the system’s failures, like escapes, can spark outrage and prompt reactive policies, says Gina Vincent, a juvenile justice expert who also co-directs the law and psychiatry program as a professor at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School.

“Judges aren’t paying attention to what works to rehabilitate juveniles, they’re paying attention to public perception,” says Vincent, who sees a concerning national trend. Lack of activities and more time in cells mean, she says, “You’re going to see an increase in aggression in facilities.”

For a system designed to provide rehabilitation, the juvenile justice framework has left many of the people who interact with it frustrated. Parents say they are left in limbo and often feel hopeless once their child is in the system. Some juvenile officers feel neglected by administrators and also say youth are given few resources to help them deal with their trauma.

For one youth who escaped and was recaptured, his accountability and rehabilitation process started once he received help outside of the system. Sconyers says those stories don’t have to be rare.

“It’s a powerful thing. It didn’t always happen for a lot of different reasons, but it’s possible,” says Sconyers. “People benefit from trauma work when it’s something they choose to do — when it’s something they have the capacity to do, when they are able to moderately engage with it, when it’s controllable for them, when it’s on their terms.”

THEO WELLING

Inside the Juvenile System

The majority of youth who find themselves in the juvenile system are accused of misdemeanor offenses. That’s true both in Missouri and nationwide.

It’s the minority — those charged with felony offenses — who are typically brought to the court’s juvenile detention center. Their intake process mirrors jail, with a full strip search, shower and change of clothes. The brown, green or orange jumpsuits they are assigned are based on factors such as high risk or trauma.

Each new detainee then waits in a small room with a sliver of light beaming from a small rectangular prism. A metal frame, board, sheet and sink are all they have during the hours they are processed in.

After they are processed, the regimen begins. Calls are limited. Lunches are isolated: one youth to a table. While school is mandated, Sconyers says it often seemed to consist of students watching movies, a claim echoed by other officers.

But that’s not always the climate, says Amanda Williams, who runs day-to-day operations at the St. Louis Juvenile Detention Center as its superintendent. Youth have limited time out of their cells but are incentivized to earn more. The center has received multiple grants for arts and recreational activities, even if volunteers are sparse. Still, every day isn’t a crisis, she insists.

“Majority of the kids who come in here, they don’t give us a problem,” says Williams.

But some of the same juveniles cycle in and out of the detention center throughout their youth, says an officer at the St. Louis County Juvenile Detention Center who spoke under the condition of anonymity. “Simply because the detention center has never done anything to help these kids out,” the officer says.

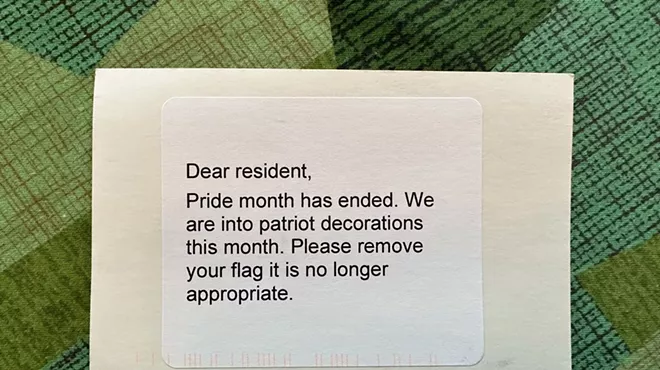

Last fall, a group of parents whose children were incarcerated at the juvenile detention facility in Clayton banded together to demand better treatment of their children, transparency and an investigation into the facility. They said youth were forced to urinate and defecate on themselves or in containers they ate from because no one let them out of their cells in a timely way. They said fights were common and staff members turned to physical restraints to control the youth.

Other officers confirm some of the allegations, saying the safety and well-being of juveniles, as well as staff, are at risk.

The unnamed officer doesn’t sugarcoat the situation. He says officers are sometimes attacked by the youth detainees. “We’re not dealing with model citizens,” he says.

He says he remembers every youth who comes through the doors in Clayton. He tries to give them a realistic view of the situation they’re in.

But he says the system can’t help delinquent youth if it’s complacent with problems such as low morale in staff, bullying by administration and a lack of services, programs and activities for youth awaiting decisions on their criminal cases.

The people running the county’s juvenile system declined several requests for an interview. In an email, a spokesperson said, “Juvenile records are generally closed records, meaning they cannot be shared or discussed outside of court proceedings. … And for security purposes, St. Louis County Courts cannot comment on internal detention center policies and Human Resource matters.”

In the city, volunteers have come to talk to youth or help them write, play or teach yoga. But, the county officer says, the majority of the time the youth are just sitting.

“Playing cards and Uno is not going to do anything here,” he says.

While juvenile detention centers in Missouri are under the jurisdiction of the courts, putting them under the purview of the state, they are funded locally. Last fall, the St. Louis County Council leveled some of its only power over the courts and called for juvenile officials to attend a budgetary meeting. Juvenile administrators took the opportunity to request additional funding to address problems related to short staffing.

St. Louis County Councilman Ernie Trakas questioned county juvenile administrators about allegations of physical, verbal and sexual assault on youth by staff. But they denied knowing of any wrongdoing. He then wrote a letter asking Missouri Attorney General Andrew Bailey to investigate.

Bailey has not responded publicly to the request, and the St. Louis County Council has not addressed the issue since.

Officers at the county detention center have received new walkie-talkies and emergency buttons. But workers still face attacks by their young charges, and the administration often forces staff to work 16-hour shifts and tries to boost morale with gift cards, the officer says.

Even so, it’s hard to get staffers to speak up about systemic issues, the officer says. “You are talking about people that need to eat. They’re not going to push the envelope.”

Catch and Release

When a youth is arrested or detained by law enforcement in Missouri, a juvenile officer submits a referral to the court, similar to the warrant process for adults.

Referrals can result in a formal decision, which comes with either detention or intense supervision, such as GPS monitoring from the courts. The decision can also be informal, which might mean diversion-related alternatives, community service, referrals to treatment services or voluntary recommendations by the court. More than 90 percent of decisions for referrals in the St. Louis area are informal.

Until last year, the overall number of law referrals to the court had decreased dramatically, with about a 71 percent drop from 2011 to 2021.

But data shows St. Louis County and city police together referred almost twice as many youth to the courts in 2023 as 2022. Last year saw the highest number of juvenile referrals in the county since 2016 and in the city since 2015.

The most common charge for youth in the state, as well as the St. Louis area, is property damage, followed by assault. The number of youth accused of homicide has more than tripled in the past 10 years, but still comprises less than 1 percent of all juvenile charges.

Despite the decline in juvenile referrals in the past decade, and the uptick in the past year, the pattern holds steady: More than 60 percent of the time when youth are referred to the court, their charges are rejected or no action is taken on the referral. The only involvement with the system is the initial contact with police.

In 2012, about 184 youth in the St. Louis area were incarcerated on a daily basis. These days, that’s dropped to about 136 youth on a given day, according to the most recent data from state and court-run facilities.

Experts say that’s a good thing. “When you incarcerate kids, it slows their development and progress of their maturity, their ability to regulate their own behavior and their sense of responsibility,” says Vincent.

Yet advocates and experts say the practice of taking no action after a referral — sometimes called “catch and release” — does nothing to rehabilitate the youth or address their needs, essentially the purpose of the juvenile system. Without good interventions, some youth escalate.

And the next time, they may well end up in a detention center. Prior referrals are considered a risk factor by the courts and can increase the chances of a juvenile official ordering a youth to be detained.

“We factor in history. If we have a youth who has multiple referrals to the court, we would treat or recommend a different course than someone’s first referral,” says Sodomka.

Sometimes parents aren’t even aware their children have been given referrals. Qunshea Jennings’ son was fighting charges at the juvenile facility but he was certified as an adult, transferred to the county jail on his 18th birthday. During the certification hearing, she heard about referrals from incidents when he was 12 that contributed to his sentence.

“This is affecting my son’s life and I never even knew about it,” says Jennings. “All these officers had interacted with my son and wrote him up.”

Some officers say they use juvenile interactions to get through to youth before it’s too late. Northwoods Police Chief Dennis Shireff says he feels the area is in a state of emergency when it comes to juvenile crime but doesn’t support constantly detaining youth. Instead, he tries to work with parents in situations that could result in tickets, summons and arrests.

“Nobody’s watching them, giving them guidance. Instead of giving them guidance, most people think that it’s easy to just lock them up. But when they’re done doing whatever little time they do, they become more of a criminal,” he says.

For many youth, being incarcerated is the only type of structure they’ve received, says Jeff Esparza, the attorney who leads the public defender’s office for youth in the St. Louis area. However, considering the harm from the system, Esparza says, the intervention needs to happen before it’s too late.

“I don’t know why it has to be the threat of a cage over your head before we can intervene with a kid who has a mental health or substance abuse problem,” says Esparza. “Jail is a horrible place, and I don’t want my clients there.”

THEO WELLING

Navigation Difficulties

Embarrassed. That’s what Karmahn Leach and many other parents said they felt when their children started getting in trouble. That’s how many parents say they felt when trying to navigate the juvenile system to support their child as best as they could.

“Not knowing my rights. His rights. What was supposed to happen. What’s next for my child? I know I’m going to be judged for it, but I need someone to talk to,” says Leach.

One day when Leach’s son was about 15, he was picked up in a stolen car and brought home, a classic catch-and-release.

“He’d get picked up or brought home and say, ‘They let me go,’” says Leach.

Soon he ended up in the St. Louis County Juvenile Detention Center, where he was held for months and never let outside. One thing Leach noticed: His skin got lighter.

In his younger years, his mom says teachers described him as bright and an old soul. But after being diagnosed with ADHD and other learning disorders, things took a turn.

“On medication he was an A/B student. Off medication it was Ds and Fs,” says Leach.

Over time it got worse. He became too active in class, and he was cited time and again for wandering around the hallways. Citations turned into suspensions. Somehow, Leach says her son found refuge at the Vinita Park Police Department, where he’d help with chores.

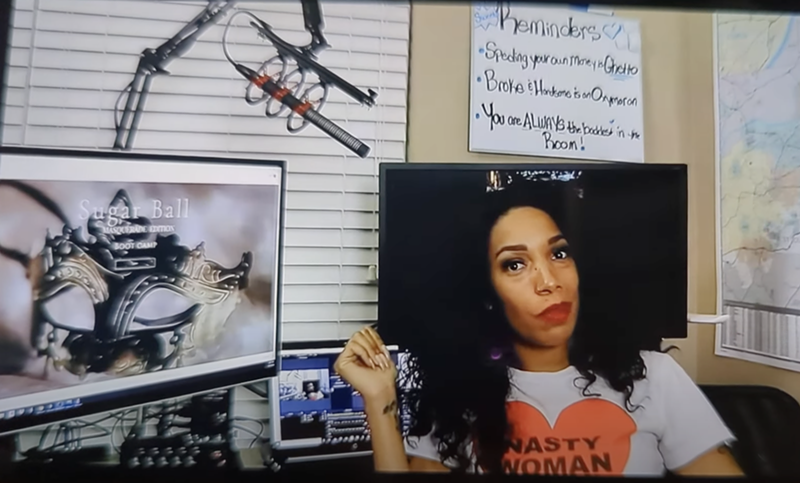

After she moved out of Vinita Park, her son’s interactions with the police turned negative. Leach now has one son incarcerated and one whose charges are pending. She started a nonprofit, Shine Bright Like a Diamond Youth & Young Adults, so that other parents wouldn’t end up in her situation.

One way she helps is by connecting parents to the services they need by working with advocates like Janis Mensah, a former member of the city’s civilian jail oversight board and juvenile volunteer with Metropolitan Congregations United.

“A lot of parents come to us not knowing even how to parent and address their youth’s issues. They come to the system thinking it will help in some type of way, not knowing the system just makes things worse,” Mensah says.

One parent, Mensah recalls, called the police when her daughter took her car for a joy ride. Her daughter ended up being detained in a youth facility. “We want a system that allows everyone to have a better quality of life and we know this system does not,” Mensah says. “It harms youth. It harms guards. The workers who have turnover cycling through that position.”

Exactly 99.5 percent of youth in Missouri and nationwide are not “offenders” or cited for breaking the law. Vincent says while that may seem obvious, it’s important to note in light of the rhetoric around youth crime. Even in Missouri, nearly 80 percent of youth who are cited for a law violation don’t reoffend.

Data shows more than 90 percent of juvenile referrals in St. Louis and the county stem from municipal police departments. Among such referrals, Black youth in the city are six times more likely to be committed to detention facilities than white ones. In the county the rate for Black youth is four times higher than white ones.

Black youth comprise only about 15 percent of Missouri’s population, but they experience a disproportionate rate of referrals, diversion, detention center sentences and certifications. Black youth also have a longer average and median stay in juvenile detention facilities than white youth.

In Missouri, administrators assess youth looking at risk factors that include parental incarceration, attitude, behavioral issues, school attendance, age at first referral and the nature of the referrals themselves. Black youth are assessed at a higher risk level than their white counterparts, state data shows.

Nearly every state uses risk assessments to determine the outcomes of juvenile referrals, says Vincent. While “risk assessments” can have a negative connotation, Vincent says they can be helpful and that judges who follow risk assessments have a lesser chance of racial bias. It comes down to the factors that are used. They shouldn’t rely heavily on factors like their parents’ incarceration or previous referrals, she says.

Often, a complete risk assessment for a youth is done only after a judge or juvenile administrator has already made a decision on their case.

“Low-risk kids end up on probation, and judges are setting conditions about the services kids should get without any information about the risk factors, which tells you what services they need,” says Vincent. “The accountability level needs to be in line with the level of risk for reoffending. Most of those kids, you’re never going to see those kids again.”

In St. Louis, one way Mensah and Leach started to combat this practice was by creating social biographies for youth in the system for judges. These bios tell a judge about a youth’s background, family support and needs — an idea Vincent applauds.

Leach says that though she’s just getting started, the people affected by the system have to come together. She’s talked to incarcerated youth who are ready to help serve when they are released.

“They just want someone they can trust,” she says. “Other people like me. No one’s going to make me feel ashamed of what I’ve been through.”

PROVIDED

Escaping From It All

One teen injured his spine trying to jump out of the St. Louis detention center in 2021. Months before, a youth who escaped from the city’s juvenile detention facility was killed while running away from police on Interstate 70.

Statewide, the number of escapes from Missouri juvenile detention centers are difficult to decipher, as some statistics include runaway data and juvenile detention facilities are not required to report escapes or attempted escapes.

Data released by the Missouri Supreme Court shows 12 escapes from the St. Louis city facility since 2021, but media reports total 15 (the detention center confirms the number at 15). St. Louis County did not report any, but media reports say two escaped. Officers at the county facility say those have been the only escapes in recent times. The Missouri Hills facility on the Bellefontaine campus in North St. Louis County operated by the state’s Division of Youth Services has also had nine escapes since 2021.

“They don’t take responsibility for how often that happens,” says Mensah. “That’s not acceptable.”

All Christian Lett could think about was getting away. That’s why he fled the police and crashed a stolen car that police spiked during the chase. He learned to steal cars after being taught by someone a few years older than him. After losing his brother through violence, he turned to anyone who could be a mentor, friend or teach him how to provide.

Transitioning from roaming the streets to being incarcerated at the Hogan Street facility was a big adjustment, he says. Phone calls were never more than about 15 minutes, and time with family was restricted.

“You’re not seeing the rotation of the sun and moon,” says Lett. “All we know is what time breakfast comes and if breakfast comes it must be another day.” He spent both his 17th and 18th birthdays incarcerated at St. Louis juvenile facilities.

At 17, Lett escaped the facility, but his recapture happened just months later. His second attempt was thwarted, and he assaulted a guard trying to escape. The guard ended up hospitalized.

This time, Lett landed in “adult jail” at the City Justice Center. It wasn’t until he started working with the Freedom Community Center that he thought he could turn his life around. (Full disclosure: The author has done some consulting work for the Freedom Community Center.)

The nonprofit provides a number of wrap-around services to justice-involved people, including therapy, court management, transportation, housing and job assistance. After FCC staff advocated for his release, a judge allowed the organization to serve as Lett’s sponsor, ensuring to the courts he’ll be law-abiding while his case plays out. Lett completed FCC’s six-week program centered in restorative and transformative justice techniques, and remained involved with the organization’s advocacy. He now works in the restaurant industry, and one day, hopes to be a chef.

He often speaks in third-person when addressing his past — remorseful but accountable, he says. His friends, hangout spots and, most importantly, his mentality all changed, he says.

That’s the dissociation Sconyers, the psychologist, worked to address with youth.

“We isolate the behaviors and we don’t look at whether the context and conditions these kids live in are appropriate for their survival,” says Sconyers.

This month Lett turned 20. No longer a teenager, he’s aware his young family members and friends look up to him.

“Instead of showing them the wrong way, having them watch me do stupid and lame things, I have choices and I’m choosing to do better. Not to do those things,” says Lett.

Now on probation, Lett says an intervention was necessary and speaks candidly about his transformation. By no means was it