RONAN LYNAM

SC* was at work at a fast-food joint snorting crushed-up pills in the walk-in refrigerator when his sister, the manager, caught him. At 19, he’d dropped out of college and was smoking weed all day in addition to abusing opiates.

“I was pretty miserable,” he recalls. After an ultimatum from his parents, he reached out to a friend from high school who told him about a drug rehab program geared for teens, Crossroads. At the time, SC was in Columbia, Missouri, where the program had an outpost, so he went to check out a meeting in 2011.

“I never called or anything,” SC recalls. “I just showed up, and the counselors were kind of shocked.”

It was unlike any meeting that SC had been to before. “I met all the people in the program, and they’re like giving you hugs, telling you how much they love you, and these are people I’ve never met before.”

Former members describe their first meetings at Crossroads as euphoric. “It’s 30 to 60 kids in a gymnasium chanting your name,” says one former member who joined in 2005.

The counselors, too, are young and not sober bores. “The counselors had long hair and all smoked cigarettes,” SC recalls. They cursed, talked about doing hard drugs, and wore leather knotted necklaces.

After the meeting came the phone calls and texts. Suddenly, a new batch of sober friends was at the ready, taking you for late-night hang-outs, parties, games and so much chain-smoking.

“They use a lot of love bombing,” says Christina Warden, a licensed therapist and former member of Crossroads. “… You’re just inundated with so much attention from these other people in the group, so much positive attention. And your life becomes very quickly only involved with the group.”

Within 10 days, SC had joined Crossroads’ outpatient treatment program, which was in St. Louis — and unwittingly became part of a wildly controversial group with deep local roots in addition to a national footprint.

Dozens of former members have described to the RFT what they see as problematic counseling that encouraged them to drop out of school or pick up chain smoking. Some allege blatant homophobia and traumatizing therapy sessions. Many are convinced Crossroads has crossed the line from being supportive into being a cult that seeks to control far too many aspects of its young members’ lives.

Crossroads is still operating today and has connections to many schools across St. Louis.

“We have relationships with all the schools in the area,” says Amy Weiland, program director for Crossroads. “And I mean all around St. Louis, even all the way up to Orchard Farms. If they ever need somebody to come in and talk for like speaking engagements, things like that: We’re on call. If they need us, we’re there.”

Weiland says Crossroads’ counselors are well-trained, and the program is effective, and that many things have changed since people like SC were in the program. But SC and many former members say Crossroads needs to be shut down.

“You’re really gaslit into living the way that they want you to,” says SC, who became a leader in the group. “You’re so scared of going back to using again, or you’re just so scared of the counselors not thinking that you’re in a good spot, that you’re willing to do whatever it takes to be in their good graces.”

*SC is a pseudonym. Several people spoke to us on the condition of anonymity.

The Start of Enthusiastic Sobriety

VIA SCREENGRAB

Started in the 1970s by a former felon named Bob Meehan, Crossroads uses a program called Enthusiastic Sobriety to get teens off drugs.

Meehan started the program in 1971 in Houston, where he moved after being released from prison on charges of burglary and public drunkenness, according to Atavist Magazine. The former heroin addict, who still struggled with alcohol, was hired to sweep the floors at Palmer Memorial Episcopal Church, and Father Charles Wyatt-Brown encouraged him to help the kids who would sometimes come to the church. He could tell some of them were using.

Meehan started with a small cohort of teens. But his sense of humor and, above all, his belief that to keep a teen sober meant you had to make sobriety look as cool as getting high, saw the program gain popularity, and the Palmer Drug Abuse Program, known as PDAP, was born.

In PDAP, kids — which the program defined as 13 to 25 —- were allowed to have parties, smoke cigarettes, curse, stay out late and drop out of school. There were only three rules: no fixing, no fighting, no fucking. Anything else was fair game in an effort to make kids enthusiastic about sobriety.

Many parents weren’t thrilled that their teens were becoming chain-smoking high school dropouts, but many were also convinced that without Enthusiastic Sobriety, their kid would die.

“I’ve talked to people who were counselors back then,” says Brandon Reid, who was in the program in 2001. “And that was their whole model. ‘Your son is going to die.’ My mom was willing to do anything” to prevent that, he says.

In 1978, actress Carol Burnett’s daughter Carrie Hamilton, then 15, used PDAP to get sober, and a grateful Burnett shared the story on the cover of People magazine and on the Phil Donahue Show. PDAP’s popularity exploded.

But just two years later, 60 Minutes did a piece on Meehan and PDAP. In it, Dan Rather spoke to several former PDAP counselors who said that the group was a cult that cut teens off from their families and told them that they couldn’t make good decisions, so the program had to decide things for them.

“As a matter of fact, we’re led to believe that we can’t make it without the program, which I think is one of the greatest disservices that’s done to anybody that goes through the program,” a former counselor told Rather.

Meehan also admitted that he had no statistics or accurate recordkeeping to back up his claims about his program’s success rate. He didn’t even make his patients give him their actual name when they register. Rather was astonished.

“We’re not here for names,” Meehan said. “We don’t have the time. We get 400 calls a day.”

He added, “I’ve been a con all my life. I just now I’m just using it in a good way.”

A few months later, Meehan was removed from the program. That seemingly led to a split. Even as PDAP continued to expand, with Meehan’s devotees as directors and counselors, Meehan started his own program in San Diego: Freeway, named after Meehan’s band. (At one point, PDAP had forbidden kids from going to concerts except for Freeway’s.) Meehan also started a few live-in treatment centers.

It wasn’t long before the PDAP program in St. Louis was struggling. When Meehan got wind of it, he persuaded its board to split from PDAP, and Meehan became the leader of the sobriety program, which changed its name to Crossroads, according to Atavist Magazine.

Then controversy erupted again. The Los Angeles Times wrote that teens in San Diego’s Freeway program had traded “one addiction — to drugs and alcohol — with another addiction — to a lifestyle of self-gratifying antisocial behaviors, dependency on one another at the expense of their home life, and a cult-like adoration of Meehan as the most important person in their life.”

Freeway’s board of directors voted to disband, and the San Diego district attorney opened an investigation into Meehan’s in-patient facilities. Both were shuttered.

For a while, St. Louis was Meehan’s only program, but that was enough for him to rebuild his empire. In time, he would go from that outpost to opening other branches and even in-patient rehab facilities — but once again, it was only a matter of time before controversy caught up with him.

And students in the St. Louis branch say that in the meantime, they suffered.

Getting to Outpatient

COURTESY PHOTO

SC started Crossroads’ 12-week intensive outpatient program in 2011 and says that much of detoxing from opiates was a blur. “Your nervous system is activated all the time,” he says. But he does recall that there were 16 other people in treatment with him and that it smelled like cigarettes.

“This is so weird you can smoke inside,” SC remembers thinking. “You’re sitting in treatment for addiction, and everyone is smoking cigarettes.”

(Weiland, the current program director, says previously kids “used to come in smoking. Now it’s rare to have a kid that smokes.”)

Each meeting began with a chant, kind of like how AA starts with the Preamble. SC doesn’t remember it entirely. But he does remember everyone would chant they wanted to “help others recover from the effects of mind-changing chemicals” and then start chanting “drugs, drugs, drugs, drugs.”

A counselor led the sessions. Many former members believe the counselors’ only qualifications for drug rehabilitation therapy were having completed the Enthusiastic Sobriety program and being sober.

Despite being a drug rehabilitation program offering therapy, Crossroads does not take state funding, so it doesn’t have to be licensed. Weiland says that all of the counselors are nevertheless certified through the Missouri Counselor Certification Board.

“We try to run ourselves as if we were a state-licensed program. We still do all the same things: lock our files and chart. We have a treatment supervisor who is an MSW, and we meet with him twice a week to go over everybody that’s in treatment.”

SC remembers counselors would begin sessions by pulling an idea from one of Meehan’s books — Beyond the Yellow Brick Road: Our Children and Drugs, about drug rehabilitation, or Bumper Stickers, a book about finding ways to be 10 percent happier.

A topic might be anxiety, and the counselor would ask what kids were choosing to be afraid of or choosing to attach their fear to.

“There’s very much an idea [in Enthusiastic Sobriety] that you choose what happens to you, including trauma,” Warden says. “And that you choose basically what your life is going to be. They teach you that your well-being is some expression of your spiritual condition that only they can help you with.”

Weiland disputes this. “They’re probably making reference to ‘no victims, only volunteers,'” she says, explaining that this is a misunderstanding. “The goal of it was to go, ‘Hey, look, if you’re not getting high, you’re not going to get arrested for doing drug behaviors.’ It was never meant like, ‘If you get raped then you volunteered for it.’ It was taken out of context.”

Plus, not all members had negative experiences. Former member John Moramarco says that his experience with the group was “overwhelmingly positive.”

“I never relapsed. I think I spent a total of 10 and a half weeks in intensive outpatient and then things got very good for me in my life.”

The other focus of the meeting was to get participants to reveal all their trauma, whether they wanted to or not. “There’s also a lot of putting all your shit on blast in front of the entire room of people,” SC remembers. “So if the junior counselor had a talk with me, and he thought I was doing shitty … then the outpatient counselor would use that as a reason to really dig into your shit in outpatient. There’s people talking about their deepest, darkest secrets.”

The counselors were often looking for “gnarly” stories, former members say. The wilder the tale, the more approval you got from the group.

Reid, who is now president of Pride STL, joined the group when he was 15. He remembers a girl saying that she’d done heroin at 13. “They put her on a pedestal,” Reid says.

Group members felt pressure to share stories about abuse, drug use, sexual assault and more. When Reid attended his first Crossroads meeting, he’d never done drugs before. He just liked all of the friendly people, so he stayed in the group and made up stories about drug use whole cloth. Many former members, speaking in the documentary The Group by former Crossroads member Jacob McEndollar, say they also embellished their drug use to stay in Crossroads.

Members say if they didn’t share enough about how they were a hardcore drug addict, the counselor and other members would accuse them of withholding, or “selfing-out,” which meant you were focused more on yourself than the group. Some people were forced to share traumatic stories that they didn’t want to talk about, their distress and tears proof of a breakthrough.

Anna Tripolitis, who joined in 2016, remembers being in outpatient and not wanting to talk about a time that she was roofied at a bar.

“I was accused of not wanting to get sober and not wanting to be part of the group,” she says. “I was accused of getting high and that I was hiding what was wrong with me. There was no option not to talk about anything. People detailed their rapes in outpatient. It was a lot of heavy stuff, and there was no treatment after that. You just said all your trauma, and then were told how it was your fault to a degree, which was really heartbreaking to hear.”

Reid says that he heard a lot of homophobic and racist comments in the group. He was starting to realize that he was gay and even talked to another member about it but mostly stayed in the closet for the two years that he was in Crossroads.

Reid also felt like he was excluded from truly belonging to the group due to his mixed race. “You had to be white to be in the inner circle,” he says.

“It’s bigoted in literally every way you can imagine,” says Warden, who left the group in 2005. “It’s misogynistic, it’s racist, it’s ableist, it’s everything. And homophobia is foundational. They normalized the belief that anything other than being heterosexual and cisgender is delusional and is a function of your spiritual sickness and your addiction disease.”

Weiland disputes this. She says that counselors are not allowed to use any kinds of slurs or derogatory language, and if they witness anyone doing so, they put a stop to it. “Teenagers are teenagers,” she says. “So sometimes they say stupid things, and when they do, we go, ‘You can’t say that here. That’s inappropriate.'”

Moramarco, a former member, says that he never witnessed or experienced any bigotry in the group. “There simply weren’t any gay people in the group when I was in it. So there wasn’t anything to be bigoted about,” he says.

But one member, who wished not to be identified, was in the program at the same time as Reid, and remembers an incident with Mike Weiland, Amy Weiland’s husband, who at the time was a counselor.

Another member in the group told Reid, “Shut up, fag.”

“I saw that [Brandon] was upset,” the participant recalls. Reid was sitting by himself, so the other participant went to sit with him. “And this is when Mike Weiland walked up,” says the former participant. “And he said, ‘Hey, what’s going on? What are you guys doing?'” The participant explained that Reid had been called a slur.

“And then Mike turns to Brandon, he goes, ‘Well, are you a fag?’ And Brandon goes, ‘No.’ And he goes, ‘All right then get the fuck over it.'”

Reid, speaking in a separate interview, remembers Weiland saying “something to the effect of, ‘If you’re not a fag, why worry about it?’ That was the beginning of the program, and I understood that was how they talked. That’s the type of language they used.”

Weiland disputes the allegation, although she admits that if the incident happened it was too long ago for her to have any memory of it. “Mike is my husband,” she says. “He doesn’t use language like that, so I don’t believe he did that.”

After being in the program for two years, Reid told his sponsor at Crossroads that he was gay. He remembers he was at one of the many parties that Crossroads sponsored when senior staff told Reid he couldn’t be in the program anymore.

“They insinuated I was a threat to other males in the program for overnights and things like that,” Reid says. They said it gently because Reid remembers not being sure if he was being kicked out of the program. Then they suggested he find somewhere else to go. “That upended my whole world. I’m left with no friends, right? I went from having 200 friends to zero.”

Reid was 17. “It’s no coincidence that I started using drugs at 17,” he says. “In fact, the first people I ever smoked weed with were ex-Crossroads members.”

Enthusiastic Sobriety’s Rebirth

VIA SCREENGRAB

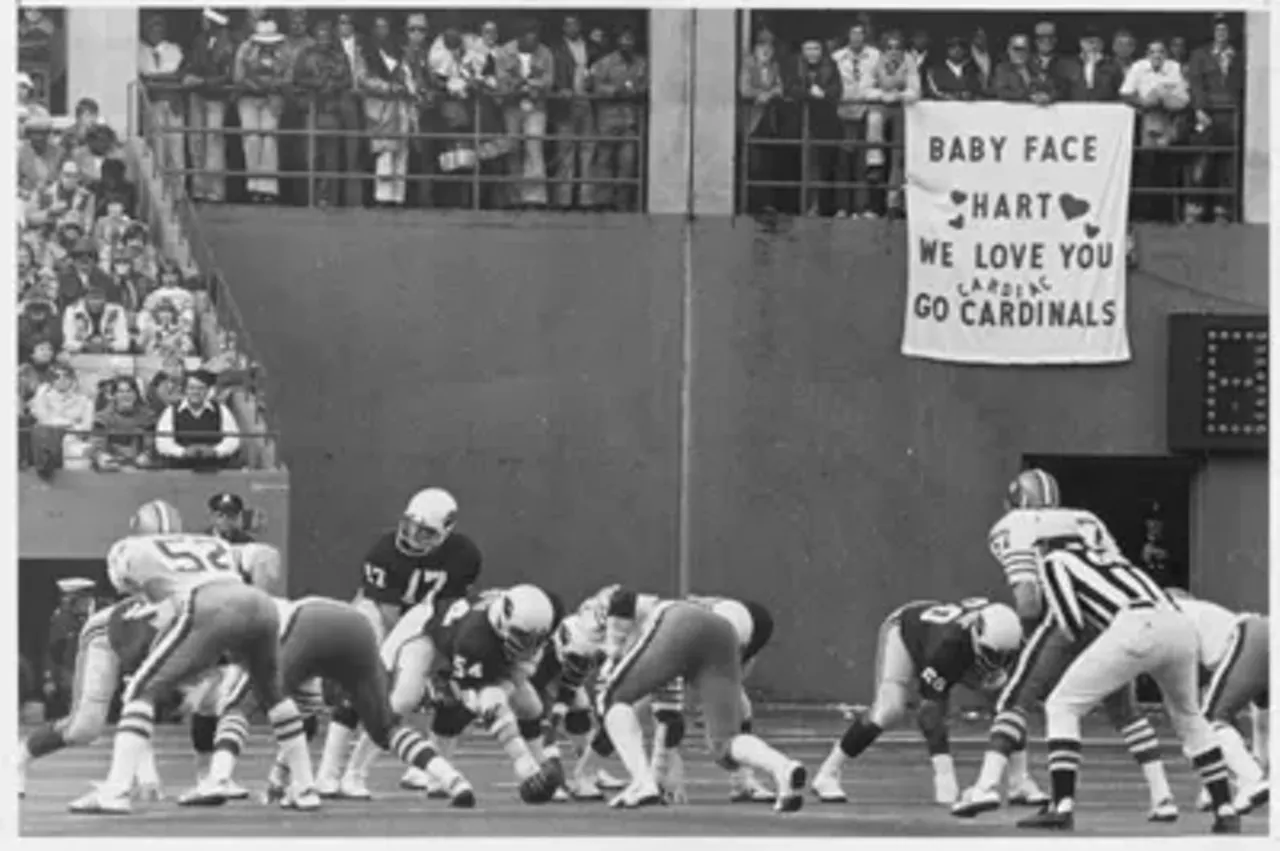

When Meehan took over the St. Louis chapter of PDAP in 1982, high schools were a big focus. Frank Szachta, who became the director, along with previous director Dave Cherry, would go to high schools and run support groups and talk to kids in the cafeteria. Many people who joined Crossroads were recruited out of Kirkwood High School, Clayton or Mehlville.

Nowadays, Crossroads has a different presence in local schools, but Weiland says it remains on call to educate the student body about drugs or set up a booth at community events. “It just depends whatever the school’s request is,” she says. During COVID-19, requests for presentations decreased, and Crossroads only gave five presentations in the 2022-2023 school year, but Weiland is optimistic that number will increase.

“We’re in the Rockwood School District, so we’re the easiest ones to go to all the Rockwood schools,” she says. “We’ve done them at Clayton High School. We’ve done them all over.”

She says the presentations are not about getting people to join Crossroads but about drug and substance-abuse education.

One participant, MT, remembers joining Crossroads in 2005. At the time, he went to Clayton High School, where he was “scooped up” in a drug bust.

“I was a 17-year-old smoking pot,” he says. “Everyone was smoking pot at the time.”

The high school told his parents that their son should check out Crossroads. MT ended up meeting with a Crossroads counselor during the school day.

“They would take you to go smoke some cigarettes elsewhere, like they had off-campus privileges,” the participant recalls. “Which is wild to think about. I did like the fact that I could smoke cigarettes. I was 17, so I couldn’t even buy them yet.”

Weiland says that going into schools like that has stopped, mostly because high schools don’t have open campuses anymore. But she would like to bring back in-school support groups. “Support groups are when we have a number of kids that are sober in one school, the school will often call and say, ‘Do you want to do a support group to support them staying in school?’ And of course we want to support them.” Not all of the kids would necessarily have to be in Crossroads, she says.

Cherry left the St. Louis branch in the 1980s (his ordeal with Enthusiastic Sobriety was detailed in the Atavist article, “The Love Bomb“), but Szachta ran Crossroads for a long time and was still the head of it in 2005 when the RFT first profiled the group. (Now Szachta runs an Enthusiastic Sobriety program in Colorado.)

As the RFT reported at the time (“Kids & Drugs & Rock & Roll,” March 11, 2005), the program had expanded to include branches in Columbia and Kansas City in addition to the one in St. Louis. The Enthusiastic Sobriety program as a whole had branches in North Carolina, Colorado, Georgia and other states, though the treatment centers all had different names. Participants who went through the program in the early aughts remember large groups, as well as outposts in other cities and an even more intensive inpatient treatment facility in Arizona that some kids who were really in need of help were sent to. The participant who was friends with Brandon Reid was sent there in the early aughts. “It wasn’t like a real facility,” he says. “It was a double-wide trailer out in the middle of the desert.”

An ABC investigation into Meehan’s drug rehab program in 2005, however, once again accused the group of being harmful for teens. As Atavist later recalled, the investigation included footage of Meehan, filmed years earlier, singing a song called “White Woman and a Ni**er” before he told kids to ignore their families and “let those motherfuckers eat shit.” (The videos had been recorded for training tapes and leaked by a former member.)

At one point, an ABC investigative team tracked down Meehan outside of the Meehan Institute in Georgia, a facility for training counselors in the Enthusiastic Sobriety message. Warden was there.

“I was standing outside with him and a news crew came running up asking, ‘Bob Meehan, how do you answer to these allegations of abuse and unethical treatment?’ And that moment broke through my essentially being a true believer of this organization and got me to start questioning it and ultimately got me to break free and leave,” Warden recalls.

The only outcome was that Meehan stepped down. By then, he was in his 60s and his son-in-law, Clint Stonebreaker, was already running the show, adhering closely to Meehan’s methodologies.

Fun felonies

The appeal of a program like Crossroads is apparent.

For starters, there are not a lot of programs catering to drug-dependent teens. SC remembers visiting another program with his dad.

“There were a lot of older people, guys in their 60s that were alcoholics and trying to stop dr