Listen. Can you hear? Ellen Reasonover is sobbing today. Today, almost 20 months removed from the Chillicothe Correctional Center, almost 20 months removed from 16-and-a-half years in hell. Steven Goldman, are you listening? Dan Chapman, you? Ellen, she wants to know. Even as she attempts a valiant smile through those tears. Almost seems God never meant for her to cry. Gave her that smooth little-girl voice that can slither its way around a conversation so pleasantly and then, unobtrusively, slink right back out. Seems that voice was preordained to pull funnies, not explain tears in a tone so strained and worn.

But it has. Explained so many tears. And so many times over. Tears of uncertainty.

Of fear. Of anger. Of anguish. Of coping. Of remembrance.

And now, today, almost 20 months removed from an existence where days and months collapsed into half-a-life’s languish too chilling to recall and too real to forget, those tears, those initial tears of uncertainty and fear, have come back to haunt her. Yes, she’s sprung now, but … now what? Now what? Today, 20 months removed, Ellen honestly doesn’t know.

“Sometimes I wish they’d never let me out,” she says today. And again: “Sometimes I wish they’d never let me out.”

Ellen doesn’t remember, though Steve Toney has told her plenty of times, but she and Steve — she then a convicted killer, Steve then a convicted rapist — rode the same bus during a 1983 journey from the St. Louis County Courts in Clayton to their respective state penitentiaries — Ellen to Renz Correctional Center in Cedar City, Steve to Jefferson City Correctional Center. All Ellen remembers from those daylong trips was being crammed in a hot bus with a bunch of sweaty men. Steve doesn’t remember much, either, but he does remember Ellen; he had been reading about her in the newspapers during his own court proceedings for rape and sodomy and recognized the young face that looked so out of place on that busload of crime-stained stories.

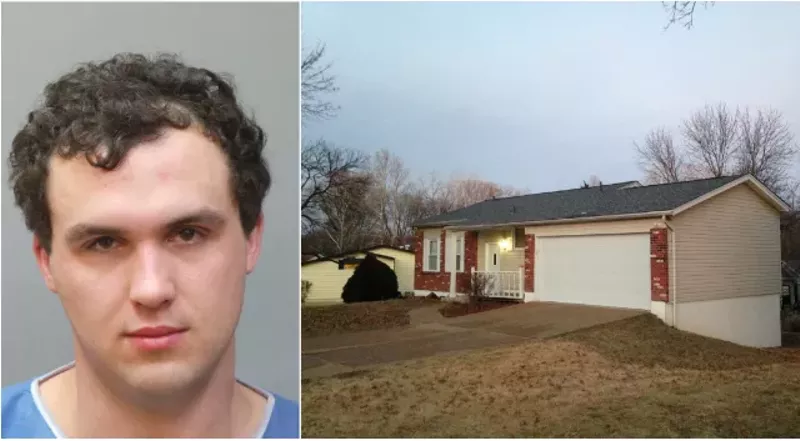

Missouri has had at least two known cases of wrongful imprisonment in which the innocent were incarcerated for more than five years. Back in 1983, both victims were on that same bus, headed for prison, Steve says. Ellen would go on to serve more than 16 years of a life sentence after her conviction for the murder of a Dellwood gas-station attendant. Ellen’s conviction hinged on allegations that Goldman, then the prosecutor, now a circuit judge, failed to let the jury know about two secretly taped conversations in which Ellen denied killing the man and that Chapman, then a Dellwood policeman and now the police chief, dangled dollars for testimony against Ellen [Melinda Roth, “Burned,” RFT, June 30, 1999]. A federal-court ruling triggered her release on Aug. 3, 1999. As for Steve, he had to wait out almost 13 years on a rape conviction before DNA evidence disconnected him from the crime in July 1996.

Now, five years later, Steve, like Ellen, has been busy just trying to get his life together. Steve would be the first to say he wasn’t a saint coming up. He had already served two-and-a-half years at Moberly — forgery, robbery, kidnapping — before the 1982 rape and sodomy of a 21-year-old Richmond Heights woman was pinned on him. Steve had been picked up on a bad-check case and, instead, found himself identified by the woman as her rapist. His alibi? He was asleep at his grandmother’s home. No chance. Next thing he knew, he’d been sentenced to two consecutive life sentences, with no parole until 2013. Then, 13 years later, a DNA test gave him back his life, and he was permitted back into society … no support … expected to get his life together. It was like abolishing slavery without reparations. Or keeping a fish out of the water too long before tossing it back.

It hasn’t been easy for Steve. No, not by a long shot. Not as easy as it was for him back in the day on those basketball courts in Richmond Heights. That was easy. He’d take that ball in his hand, and he could swear by his mother that he didn’t have the thing on a string. Nobody’d believe him. Need a 45-degree bounce pass, on the run, down three quarters of the length of the court? No problem, one-handed or two? Need a now-you-see-it-now-you-don’t crossover and a pull-up 20-footer? It was money for Steve. He’d play pickup games with the likes of McKinley grad and future Celtics All-Star Jo Jo White. Shoot around with the St. Louis Hawks. He didn’t have the height, but his arms were unnaturally long. He was a point guard who would also be his team’s second-best rebounder. Steve would drop 20 a night for Brentwood High, no sweat, and smoke a cigarette after the game. It was that easy.

But this, this is different. What’s easy about being five-and-a-half months behind on rent? About being behind on utilities? About using what little money you have in your pocket on public transportation? About being 54 and looking for that permanent job (Steve works 24 hours a week driving cars at a rental agency)? About depending on other people for survival — 20 dollars here, an extra 30 there?

Ellen faces similar challenges. Her clothes don’t fit these days; they’re all too big. “I don’t care,” she says. “I don’t ever have any money to eat nothing.” She had an assembly-line job and an apartment, but then she was laid off. She lost the apartment. Rent was just too much. She has $35 in her legal-defense fund. She wants to take 20 out so she can fill up her gas tank. Maybe borrow 10 from her mother. Another 20 from her sister. Just something to get some food, maybe. She received a letter from New York City a few weeks ago. Enclosed was a contract to purchase her life story — movie rights, book rights, series rights, that sort of thing. More important, it held the potential for money. But Ellen hasn’t had time to really even read it, and, of course, she doesn’t have the money to take it to a lawyer. “I’ve been so stressed. I just, I don’t know …” her voice trails off. Ellen had been living with her daughter, Charmelle Bufford, when she had her own place. Now Charmelle stays with Ellen’s mother.

And Ellen? Where does she stay? Sometimes at her mother’s. At her sister’s. At one of her girlfriend’s. But she doesn’t want to be a burden. She never wanted to be a burden. Sometimes she sleeps in her car.

“It’s a very difficult road, especially when you’ve been in prison for a lot of years,” says James McCloskey, whose New Jersey-based Centurion Ministries helped free both Ellen and Steve.

“It usually takes a good year, maybe two years, for them to find their place and get their feet on the ground and understand their environment and the world around them,” McCloskey says. “First of all, they have got to develop some sort of financial footing so they can ultimately lead self-reliant, independent and productive lives. Now, that requires employment, gainful employment that has some kind of upward mobility to it. That usually is hit-and-miss, and it takes a few tries to latch onto the right position. And there’s always psychological counseling that you should go through, because there’s a lot of anger in people, whether they admit it or not. A lot of them try to hide the anger and repress it because they believe, and I think rightfully so, that if they show their anger, then the people will start to believe, well, maybe the person did what he or she was in prison for.”

Anger. Steve won’t show it; he never has been one to dwell on his misfortune. He doesn’t dwell on the friends he lost while in prison; he doesn’t dwell on the family he lost while in prison. How many times will people ask him whether he’s bitter? And how many times has he told them he’s not? Do they want him to be bitter? Well, he is, deep down. “Bitter? Yeah. Angry? Yeah. Mad? Yeah — as hell. See, I always believe. I’ve given out a long time ago. I just don’t have no more. I can go only so far, do so much; I can only pray and keep believing. I’ve given out a long time ago, but I just don’t give up. You, yourself, can only take so much. The strength comes from not giving up. With every difficulty comes relief.” So, bitter, yes, but usually he won’t say it.

He’s a praying man, but he’s a proud man, says friend June Jeffries; he won’t admit the hurt. He’ll hide the scar. Look at him. Look at the way he walks — he’s always had that strutting gait. She remembers when he used to take her roller skating or to those block dances in Richmond Heights, where they would block the whole street off and just dance to Smokey Robinson, to the Supremes, to Sam Cooke, to Marvin Gaye. He had told her cousin way back then that June would be his friend one day … he’s a proud man. And this proud man will keep his emotions in check; instead of venting, he’ll pick up his copy of the Quran from his bedside stand and read “The Expansion.” The last two lines of the verse? So, verily, with every difficulty there is relief/Verily, with every difficulty there is relief.

Like 35 other states, Missouri has no mechanism to compensate the wrongfully convicted. State Rep. Betty Thompson (D-University City), though, has sponsored a House bill that would do just that. Indemnification statutes are a legislative phenomenon so scarce that even some attorneys are oblivious. “Wow,” says Dan Gralike, deputy director of the Missouri Public Defender Commission, when briefed about the bill. “Is that some kind of award?” Closely tailored to resemble a New Jersey statute, the bill, which hasn’t made it to the House floor yet, proposes a cap of $20,000 or twice the victim’s preconviction salary for each year of wrongful imprisonment — a higher compensation cap than most, which swing from the federal limit of just $5,000, regardless of duration of incarceration, to New York’s unlimited-damages policy.

Claimants must shift gears from the criminal to the civil arena in order to qualify under Thompson’s bill — that is, after proving reasonable doubt of guilt to earn emancipation, they must show “clear and convincing” evidence of innocence to qualify for any damage awards. The task would prove smoother for someone like Steve, who was unequivocally exonerated by DNA evidence, and thornier for Ellen, who won her freedom through the dramatic introduction of exculpatory evidence that cast doubt on her murder conviction. Because her bill was originally drafted with Ellen in mind, says Thompson, she may push to include Ellen’s name specifically in the bill’s final version to ensure her an award.

On their release, both Steve and Ellen had the option of filing for civil damages, but, attorneys concede, the prospects for success are limited — the very reason Thompson’s bill is so crucial. The immunities provided to police, prosecutors and judges and a fault-premised civil-law structure team to make damage awards excruciatingly rare at best. “A lot of these people who that this has happened to, it isn’t any one person’s fault,” explains Adele Bernhard, associate law professor at Pace University in White Plains, N.Y., who tracks compensation legislation across the nation. “If somebody got raped and they all of a sudden saw you walking down the street, and they said, ‘Oh my God, that’s the person who did it,’ and if they were a credible person, and they tell that to the police, the police have a responsibility to arrest you.

“And if the jury convicted you based on that person’s identification, there would be nothing wrong with the verdict; it just so happens that you didn’t do it. So, 18 years later, when they do the DNA test and they prove it wasn’t you and you were right all along, yes, the victim was wrong, but she just made a mistake. So, generally, unless the police have torn up police reports or hidden witnesses or suggested that people lied or tortured confessions out of people, then nobody’s done anything wrong. They’ve all gone along with the prosecution the way they normally would; it just happens to be the wrong person.”

Indeed, Steve, a victim of mistaken identity, failed in his attempt to collect civil damages soon after his release. Ellen plans to announce her own civil suit, which she says will be filed later this month by New York attorney Barry Scheck. Scheck couldn’t be reached for comment.

There have been some spots of civil success. An Illinois foursome known as the Ford Heights Four who spent a combined 65 years in prison collected a cool $36 million from Cook County two springs ago in a wrongful-prosecution lawsuit. Ellen and Steve, who knows what they’ll get, if anything? Thompson’s bill, Steve’s only realistic shot, isn’t exactly gaining legislative momentum, and Ellen, she can only wait and see what unfolds in the coming months. And until then? That’s the question.

“I just wish I had money,” Ellen says, drying her eyes, “from the movie deal, from the lawsuit, from the bill, from something. Then maybe, maybe I’d get me an apartment. I just want enough to pay rent, electric, gas, phone bill, get enough to eat. That’s all.”