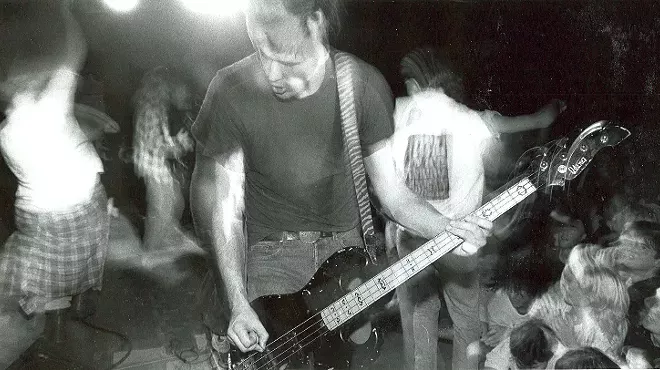

SEAN DERRICK

Editor’s Note: Garrett and Stacy Enloe love music and actually met at a concert at the now-shuttered American Theater (they were seeing Jackyl). Marriage followed in 2000, and then in 2016, they won a piece of St. Louis music history: a portion of the Mississippi Nights awning. That spurred Garrett to make a Mississippi Nights fan page on Facebook for the venue that opened in 1976 and shuttered in 2007.

The page soon had 2,000 members recalling working at, playing or attending concerts at the venue. That energetic fan base inspired the book Mississippi Nights: A History of the Music Club in St. Louis, which came out in October. Part scrapbook, part oral history, the book also features a comprehensive list of every band that ever played the venue. It shares photos, ticket stubs, concert fliers, setlists and band photos, as well as stories like the one about the time Hole performed and Courtney Love said she was sick and fell over, or that time Nirvana nearly started a riot. It also highlights the characters of Mississippi Nights, including the Cookie Lady and Beatle Bob.

Below are excerpts from the book that capture what made the all-ages venue an iconic part of St. Louis for 30 years.

Welcome to Mississippi Nights

PAUL HILCOFF

Los Angeles had the Whiskey a Go Go, Troubadour and the Roxy Theater.

New York City had CBGB, Studio 54 and the Palladium.

St. Louis had Mississippi Nights.

Mississippi Nights, appropriately promoted as “The Music Club of St. Louis,” operated from 1976 until 2007 and was located in the historic Laclede’s Landing section of downtown St. Louis at 914 North First Street.

To get to Mississippi Nights, you drove past the Gateway Arch grounds, under the ornate arches of the Eads Bridge, over several blocks of cobblestone streets and past century-old buildings that once housed fur traders, slaughterhouses and dry-goods warehouses. The old, weathered brick building had character with its arched doorways and windows. The color variation in the bricks suggested that once there were more windows and doors, removed for unknown reasons. The Eads Bridge, spanning the mighty Mississippi River, could be seen from the parking lot on the south side of the building.

Upon entering the wooden door on the right, you were in a vestibule surrounded by signed 8×10 band photographs in black frames. To the left, past the second door, were a couple of video games; a pinball machine; a cigarette machine; some round, white-topped tables with black, wooden chairs; a small bar in the corner; and another set of doors that sometimes opened to accommodate large crowds. It was a short walk forward to have your ID checked, hand stamped and ticket torn.

To the right was the bar with wood paneling up the back wall, neon beer signs and open shelves of liquor and glasses. Following a sloped walk down past two tiers of additional tables and chairs on the left (the first tier also housed the sound mixer), the walkway opened, revealing restrooms and the underage section (the raised area often referred to as the “kiddie corral”) on the right, and to the left was the dance floor and stage.

The stage was covered with parquet flooring and elevated about three and a half feet off the floor. A small walkway to the right of the stage led to the back door and, behind the building, steep metal steps where the bands loaded out their equipment at the end of the night. (Fortunately for the crew, they were able to load in through the front door into the empty venue in the morning.) Sometimes, metal barricades blocked the front of the stage, but often you could press yourself right up against this platform in front of your favorite band.

Chuck McPherson* Remembers…“What was special about Mississippi Nights? The people. The atmosphere. The smell. The experience. You could not only see a good show but meet the artist. It was seeing up-and-coming bands before everyone else, as well as bands on the way down. It was all-ages shows in a bar atmosphere. I was underage and limited to the floor and the side of the stage for much of my time there, but it didn’t matter. To borrow the phrase, it was the most magical place on Earth. Mississippi Nights was one of the places where I spent much of my mid-teens to early adult years. I made friends at the club that I still have to this day. It’s a place I will never, ever forget. No other club can compare. 914 North First Street will be in my heart until the day I die.”*Mississippi Nights patron

Several factors contributed to the longevity and popularity of Mississippi Nights. [The venue] did an excellent job of booking shows and showcased a variety of music genres, unlike many clubs that catered to one genre. The sound system was incredible, appealing to the audiences and the musicians. The staff was welcoming and made the club feel like a second home to many. Finally, you were able to get up close and personal with the bands — in front of the stage as they played, at the bar while they drank, or outside as they came and went.

Being the best place to experience music in St. Louis for so many years, countless people forged new relationships and memories at Mississippi Nights. Many concertgoers developed friendships that would last a lifetime with the staff or fellow patrons. Some went to the club on first dates or even met their spouse there. The memories run the gamut from meeting bands, the friendly staff, amazing performances and crazy incidents (some involving liquor).

Mississippi Nights was a treasure in St. Louis. Unfortunately, as time passes, memories fade. … So, we preserve those memories and the music that Mississippi Nights produced for 30 years with this book.

Angela Prada* Remembers…

“Mississippi Nights was lightning in a bottle. Having worked there, I have to say everyone felt they were part of the show, not just watching it. There was a true sense of community and a love of music between patrons, staff and the bands. No one complained about it being hot, crowded, smoky or that they were eating popcorn out of a trash can. They were there to see the show.”

*Mississippi Nights server

1867: Pork Packers

Although the building may date as early as the 1830s, the first confirmed business in the Mississippi Nights building does not appear in records until 1868. James Reilley & Co. Pork Packers may have lasted for less than a decade, but the business is responsible for one of the signature features of the club, the floor that began to slope as you passed the ticket window.

Documents from 1868 declare the building was owned by James Reilley, David A. Spellen and Michael McEnnis. The 1874 book St. Louis: The Commercial Metropolis of the Mississippi Valley contains an advertisement for James Reilley & Co. Pork Packers, located at 914, 916 and 918 North Main Street. “Pork Packers” is a euphemism for a slaughterhouse or meat processing facility. The building’s signature slanted floor, eventually bordered by the bar and the over-21 seating section, was designed to drain blood from animal carcasses.

Becoming Mississippi Nights*

JOHN KORST

Steve Duebelbeis started Mississippi Nights after attending live concerts at clubs in Springfield, Missouri. He appreciated how the clubs featured more than just cover bands. Duebelbeis looked at the space, which was previously a nightclub called On the Rox, and bought the building on August 30, 1976.

Duebelbeis sold the venue to real estate investor Rich Frame in 1979. He owned it until it closed in 2007.

*Editor’s note

1983: The Grandmother of Rock & Roll

Pat Lacey’s name is connected with Mississippi Nights more than anyone who worked there in the club’s 30-year history. She began her association with the club by taking her daughter Sarah and her friends to concerts at Mississippi Nights.

On the night of the X show, October 24, 1983, [owner] Rich Frame asked Lacey if she knew of anyone who would want an office job at the club. Frame knew she worked as a nurse, so he was surprised when she responded, “Yes, me!”

With her husband laid off and their daughter Susan in college, Lacey needed another job to make ends meet.

Lacey admits she did a terrible job in her interview with Frame. She kept reinforcing that she didn’t have any experience and was uncertain she could do the job. However, with his knack for reading people, Frame had the confidence in Lacey that she lacked, and he hired her on the spot.

Frame speaks of Lacey with reverence. “She did everything,” he asserts. She juggled nursing and rock & roll for four years before leaving her nursing job to dedicate her time to the club.

Lacey broke down her duties. “I wrote the checks, sold tickets, did the inventory and the ordering. I did the pouring costs, which was how much we spent on alcohol and whether we made a profit or not, and I did the same thing with shows. When [manager] Patrick [Hagin] left [in 1990], I stepped in and took on a lot more. I was doing everything that he did: doing the contracts, going to the bank, making sure the shows were advanced, so that we knew what time bands were coming in and what time they wanted to be fed, etcetera,” Lacey says. “I was the den mother there. I took care of the bands. A lot of them became my friends.”

ANDY MAYBERRY

“Lacey had many jobs,” says manager Tim Weber (1998- 2007), “but arguably her most important job was to advance the shows.”

She organized hospitality events for bands and their crews, including solving problems before they arrived.

Jason Voigt* Remembers…

The only event I attended at Mississippi Nights was Joan Jett & the Blackhearts on October 27, 2006. Eagles of Death Metal opened. They rocked the house, but there were other things on people’s minds that night; that was the same night the St. Louis Cardinals won their first World Series since ’82. There were no TVs on, and this was before smartphones. Suddenly, people were yelling right in the middle of a song. Everyone knew it happened. I left the concert early and joined in on the fun outside as people were happily shouting and cheering on the Landing.

*Mississippi Nights patron

“She’d call up and say, ‘Do you really need four gallons of hummus?’ She was able to do it in the nicest possible way so that every band that showed up was in a good mood when they got there,” Weber says. “If you screw that up, every band shows up in a shitty mood, and the days are wrecked. So that tiny little thing of making the bands understand ahead of time that they were going to be cared for at least gave you a running shot to start every day pretty good.” Lacey made the bands happy, everyone’s job more manageable, and Mississippi Nights more successful.

“Absolutely nobody tops the legend that is Pat Lacey,” proclaims Mississippi Nights patron Chuck McPherson. “She was the heart and soul of the club. … She always treated me and my friends like her children. She got to know us on a first-name basis and was supportive of us in our love for music.”

Patron Michelle Weber Rigden says, “Pat Lacey was my concert mom. She was so kind and nurturing, but I also knew she would take my ass out if I misbehaved as a minor.”

Patron Wade Monnig says, “Pat Lacey was always amazing, always so nice and sweet. I’d always go see the Alarm at Mississippi Nights, not just because they were a great band [but] because Pat was so passionate about them. I wanted to support her!”

Lacey decided to retire the year she turned 65, thinking that’s just what you do at age 65, and at the end of 2002, she did.

In May 2003, Lacey entered Mississippi Nights with a gift of strawberry shortcake for the staff. She quickly learned that her replacement was having problems managing the office. For example, he wrote checks out for every invoice without checking if they were already paid.

COURTESY RICH FRAME

Before long, Mississippi Nights had substantial credits with the vendors. Tim Weber asked Lacey to return, and she agreed to come back two days a week. After that, she didn’t think of retiring from Mississippi Nights again and worked there through February 2007. “The Nights officially closed at the end of January, but I needed to clean out the office,” she remembers.

At 84 years old in 2022, Lacey wishes she could still be working at her beloved Mississippi Nights.

“[Pat Lacey] was the grandmother of rock & roll,” says Tim Weber. “She cared more about more people and more bands than anybody I’ve ever met in my life.” He adds, “I still get tour managers at the Old Rock House that remember Pat Lacey.”

Tony P. Pona* Remembers…

“I worked at Mississippi Nights for 10 years, so I have many memories of the place. One that stands out is the night of [the] Alvin Lee [concert] when Bon Jovi’s Richie Sambora was sitting stage right in a packed house [on October 31, 1984]. I believe [Bon Jovi was] playing in town the same week of Alvin Lee, got in early, and [was] bummin’ in the city. Absolutely every lady in the place knew who Sambora was. He was just there to see Alvin Lee. I worked secondary security. We kept the public away from Sambora (for the most part). He did sign and take a few pics, though.”

*Mississippi Nights stagehand and security

1990: The Eyes/Pale Divine

Opening an exciting new decade for St. Louis music, Richard Fortus was the guitar player of arguably the most popular local band in St. Louis, the Eyes. Fortus founded the band six years earlier when he was merely 15 with vocalist Michael Schaerer, bassist Steve Hanock and drummer Greg Miller (later in Radio Iodine and Suave Octopus). Hanock left the band before 1990 and was replaced with Dan Angenend.

The Eyes rose through the ranks of local bands in St. Louis, constantly playing at the under-21 club Animal House, Kennedy’s 2nd Street Company (that would come to be known simply as Kennedy’s) on Laclede’s Landing, and Mississippi Nights.

DEBBY MIKLES

One night in 1990, record executive Jason Flom saw a line of people waiting in the rain to get into 1227, a club on Washington Avenue in downtown St. Louis, to see the Eyes. Flom was famous for signing hard-rock bands like Skid Row and Twisted Sister. So he decided to send his assistant to Mis