Courtesy 314 Bird Studios

Edrar ‘Bird’ Sosa vividly remembers the day he first heard about the headless child who would go on to become the city’s most notorious cold case.

But it wasn’t cold yet. It was 1983, and Sosa was only about 10 years old, growing up in north St. Louis not too far from the house where the child’s mutilated body had been found.

“My mom told me, ‘You have to be in before it gets dark because they’re cutting little kids’ heads off now,’” he says. “That stuck with me … I didn’t understand it.”

The girl’s remains still have not been identified, something that for many is as shocking as the crime itself.

Sosa’s mother took him, as so many parents did in those days, to the mall to get fingerprinted and have his blood type taken. But that wasn’t the end of it for the two. Over the years, they’d talk new developments and wonder who Jane Doe really was.

Courtesy 314 Bird Studios

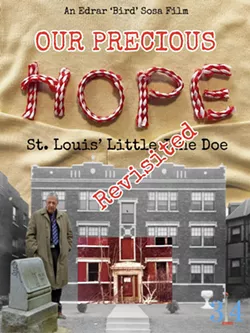

But Sosa wasn’t satisfied with talk. This month, he is releasing Our Precious Hope Revisited: St. Louis’ Little Jane Doe, a documentary about the case from his production company 314 Bird Studios. That documentary will be available to stream on Amazon Prime later this month and has been accepted into film festivals, including the Jackson Film Festival and the Chicago Indie Film Awards. In it, Sosa has not only covered old ground but also clarified misconceptions and applied new advances in criminology, such as forensic genealogy, to try and discover the victim’s identity.

The St. Louis Jane Doe cold case has fascinated and horrified St. Louisans for the last almost-40 years. It starts in February 1983 in the basement of 5635 Clemens Avenue, a then-vacant apartment building in northwest St. Louis about a mile north of the Delmar Loop. Two men entered with the intent of finding a metal pipe that they said they intended to use to repair a car.

Courtesy 314 Bird Studios

But instead, they discovered the headless body of a young Black girl. She wore only a yellow sweater and had her hands bound behind her back. Police searched for her head and cross-referenced missing-persons reports to no avail. They couldn’t discover her identity, and eventually, the case went cold.

In 2004, the Riverfront Times published a feature, “The Case That Haunts,” on the Jane Doe, who has also garnered nicknames such as Hope, Precious Hope and the Little Jane Doe. Sosa says that the piece helped renew his interest in the case almost 20 years ago. Still, the documentary might not have come to be. In 2016, his mother passed away, and he told himself he should follow through and finally make it. Then, in March of 2021, he got a bad case of COVID-19.

“I told myself if I live, I was going to make this documentary,” Sosa says. “I got out [of the hospital] after about six weeks. I sold my Mercedes, bought all the equipment for it and said I’m going to make it.”

Sosa was not a filmmaker, he worked primarily in hotel management. But Sosa wasn’t an entirely unlikely candidate to make the documentary. He holds an undergraduate degree in criminology and criminal justice from the University of Missouri-St. Louis. He began the process by reaching out to the police, feeling like he’d struck gold when he set up an interview with Joe Burgoon, a cold-case investigator for St. Louis County Police and one of the original detectives on the case, thanks to a chance connection.

Courtesy 314 Bird Studios

“The head of homicide actually watched my first one, and then they wanted to be a part of it,” Sosa says, explaining he’d first produced an hour-long piece comprised of four interviews before diving into the full documentary, which now runs over two hours. Sosa dove into all the pre-existing reporting, noting the inconsistencies among accounts and especially with Burgoon’s account of the events.

“So that changed my mentality,” he says, “[It led me to] put a story together with a timeline and actual verified information.”

Several setbacks have come to define the Little Jane Doe case over the years. Two stand out starkly. First, the sweater that the Joe Doe had been found in had been sent to a psychic in Florida and never returned. Second, the body had been buried in Washington Park Cemetery, but when investigators went to exhume her in 2013, the grave couldn’t be found. (Eventually historians helped identify the correct grave.)

Sosa dug into these incidents, discovering a previously unknown receipt from the psychic that implies the sweater was lost in the mail. He also believes that Jane Doe’s body might have been purposefully put to rest without proper markings to discourage grave robbers.

Courtesy 314 Bird Studios

But he found himself baffled by a piece of commonly reported information: that Jane Doe had spina bifida, a birth defect where a portion of the spinal cord is exposed.

“If you read any reports, people just made up … that she had spina bifida occulta,” Sosa says. “I have the autopsy myself. It was never in the autopsy.”

The documentary also features CeCe Moore, a genetic genealogist who frequently works with the police. Though he can’t yet fully share their findings, Sosa believes that Moore and the police are getting close to discovering the identity of Jane Doe.

In total, the documentary features interviews with eight individuals who are either close to the case or are experts in some relevant area related to the case. While Sosa is glad to be sharing the finished product with the public, he says he could have kept digging into the details and adding on to the film.

“Honestly,” he says, “I don’t know that I will ever be done until she’s identified.”

Email the author at [email protected]