Mo. Dept. of Corrections

Updated with graph of prison hierarchy.

You’ve probably heard by now that convicted kidnapper and child molester Michael Devlin was stabbed last month in a prison in Cameron, Missouri.

Devlin — as you’ll recall — made international news back in January 2007 when he was arrested with kidnap victims Shawn Hornbeck and Ben Ownby living in his Kirkwood apartment. Hornbeck had been missing for four years, Ownby for several days.

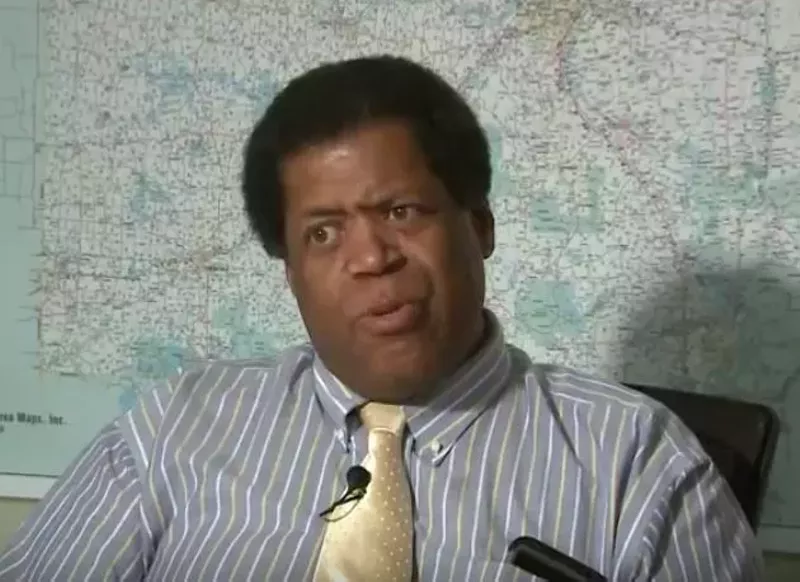

Fellow inmate Troy L. Fenton readily admits stabbing Devlin out of anger for Devlin’s crimes. Fenton even named the two shanks used in the attack “Shawn” and “Ben” after the two abducted boys. Devlin survived the assault, though the incident only reinforces concern for his safety.

Fenton, by the way, is in prison for robbery and shooting at a cop. Which begs the question: Does that make him a more respectable person than Devlin?

Based on the hierarchy inside prisons, the answer would definitely be “yes.” That structure places convicts like Fenton near the top of the pecking order and men like Devlin — who has both notoriety and sexual assault convictions working against him — at the bottom.

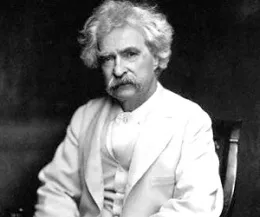

“There’s something of an informal pecking order in prison with guys who commit the most violent crimes higher up in the order and sex offenders — especially pedophiles — pretty far down,” says Bill DiMascio, executive director of the Pennsylvania Prison Society, a social justice organization that’s advocated for prisoners since 1787. “In many cases, the safety of those at the bottom can be in jeopardy.”

Although prison officials are loathe to admit such hierarchy exists, they’ve tacitly acknowledge it on previous occasions when they considered moving Devlin out of state or changing his identity for fear for his safety.

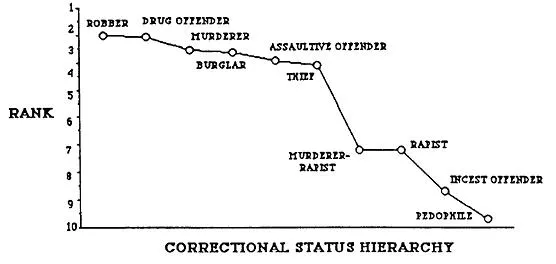

Most scholarly research on inmate hierarchies generally have to do with sexual relations and rape in prisons. A 1989 study looking into the criminal hierarchy inside penitentiaries came up with the following graph — with robbers, drug dealers and murders near the top and pedophiles at the very bottom.

Prison Journal, 1989 69:73, Michael Vaugh and Allen Sapp

Anecdotal evidence suggests that non-sexual attacks against well-known sex offenders, like Devlin, can also move the inmate who perpetrates the assault further up the ladder.

“Most inmates don’t talk about their crime,” DiMascio tells Daily RFT. “That’s especially true for sex offenders. In state prisons, though, their past lives are harder to conceal. These guys come from the same area. They know what’s going on beyond the walls. And what appears to be an attack out of the blue, can definitely be provoked from something that occurred outside.”