BRADEN MCMAKIN

Two friends got famous making pancake art. Then came the split

BRADEN MCMAKIN

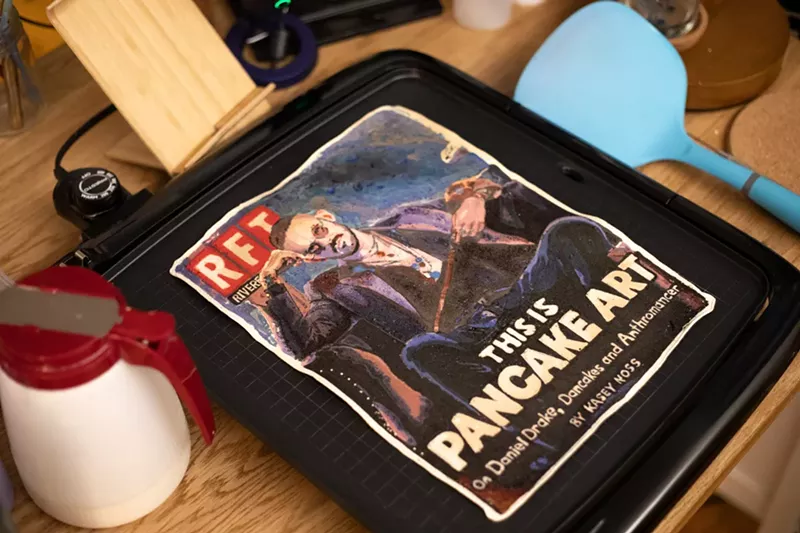

In September 2018, at the United Square Shopping Mall in Singapore, two friends sat down to play a game. Well, first, they sat down for a cup of coffee between rounds of crafting elaborate pancakes for six-year-olds. To most people, the second half of that sentence might seem odd. But for Daniel Drake and Hank Gustafson, this was business as usual since founding Dancakes, the world’s first name in professional pancake art.

If Gustafson had his way, the two of them wouldn’t have gone to a cafe in the first place on the grounds that homemade coffee was cheaper. But Drake loved cafes, and Gustafson loved Drake. As they sipped their overpriced coffee, Drake looked up at Gustafson with a strange look in his eye. He knew what Drake would ask before he asked it.

“Wanna play Anthromancer?”

Anthromancer is the board game that the friends had invented in their time off from flipping pancakes for celebrities and billionaires (and schoolchildren in Singapore). Drake had the idea for Anthromancer on the flight home from a television appearance in Brazil three years prior, and they’d adopted it as a pet project. They’d play it between gigs, quibble endlessly over its mechanics and text each other at odd hours of the night with new ideas. By the time they reached Singapore, the two had played hundreds of iterations of the game.

The cafe’s floor-to-ceiling windows flooded its mahogany interior with light as Drake and Gustafson set up their makeshift board and cards. After an hour and a half of intense gameplay — Drake won twice, Gustafson once — Anthromancer began to garner some attention. It wasn’t nearly as much as for their pancakes, but their contacts in the city and even some passersby became engrossed. One even asked if the mall sold it. As the duo began their second pancake art demo of the day, Gustafson felt profoundly satisfied.

“That was a beautiful moment,” he says. “We’re halfway around the world, and we’re playing this board game that we made in a cafe, and we’re here because we’re doing pancake art.”

Neither knew at the time that the game would drive them apart, end a decade-old friendship and propel Drake into a business venture even stranger than pancake art. How it happened is clear, but the two still argue over why. Things were simpler in 2018, but even then, Gustafson could see a reckoning coming.

“I’m like, this game is pretty good, and if we do this right, it could take off,” Gustafson recalls. “And I know, for a fact, Dan’s gonna have to focus on it.”

BRENT HOLZAPFEL

When Drake first tried his hand at pancake art, it was a side job, not a calling.

The year 2009 found him working the night shift at Courtesy Diner, a greasy spoon on South Kingshighway Boulevard with edible food and adequate service. Prior to Courtesy, Drake hadn’t had any professional experience in the kitchen. As a teenager, he passed his time doodling on his assignments instead of turning them in. He wrote and illustrated his own comic books. He graduated with mediocre grades and skipped college, hungry for “the simple freedom that came with working paycheck to paycheck.” He tried his hand at music and founded a band, his first of three, called the Psychedelic Psychonauts.

He demanded a spontaneity from life that it hadn’t afforded him thus far. But Drake also needed to pay the bills, which is why at 19, he applied for a job as a fry cook.

Drake got stuck with the slow shifts until he could earn his place as a cook. They say time is money, but without enough customers to yield substantial tips, Drake was left with a lot of one and little of the other. He had hoped Courtesy would support one artistic career. Little did he know, it would jumpstart another.

One particularly slow night behind the griddle, Drake recalled the advice of a coworker who told him that adding little mouse ears to the pancakes usually boosted tips. The only customer in the diner was a man named Chad, who seemed to be having a bad day. Drake whipped up a simple smiley face pancake for him. Chad left him $15.

Drake would come to view this as a “light-bulb moment.” He began to push the boundaries of what pancakes could look like, starting with their shape. A friend showed him how to layer the batter so that some parts of the pancake would darken before others, allowing his designs to become increasingly elaborate. He developed a small following at the diner. People would come for the pancake guy, asking for all sorts of intricate designs. Drake would deliver every time.

A few years passed in this manner. Drake made pancakes. He churned out stars, dinosaur eggs, jellyfish and even the infamous meme-turned-NFT Nyan Cat to eager customers. He also hadn’t given up on his music career. In the late summer of 2013, Drake wanted the Psychedelic Psychonauts to film a music video. A coworker put Drake in touch with Gustafson, an amateur videographer.

The music video never happened, but it was the start of a decade-long friendship.

In November 2013, when he was 23, Drake’s life changed forever. One of his creations went viral on Reddit. It was a rendition of the iconic Mario Bros. mushroom that he’d posted to Facebook almost seven months prior.

“Daniel, aka ‘that guy from Courtesy Diner that does the thing,'” the post read. Under it, Drake sports a goofy grin as the pancake that would make him famous sits unassumingly on the griddle behind him.

Drake was in bed when he first went viral. It was late afternoon, and he was resting up for a late shift at Courtesy. Normally, he’d wake up to see the sun setting on his apartment in Tower Grove. Instead, he arose to a barrage of texts from friends, family and coworkers, all with the same thing to say: “Dan, you’re all over Reddit.”

Next came a whirlwind. Drake’s Facebook page, Dr. Dan the Pancake Man, quickly amassed a substantial following. The Today Show flew him out to New York City the day before Thanksgiving, and his pancake portraits of hosts Matt Lauer and Al Roker were broadcast live to millions. When he returned to St. Louis, fans flooded Drake with requests to appear at their birthday parties and brunches. Within days, he went from scrappy fry cook to local celebrity.

BRADEN MCMAKIN

As his star rose, Drake was allowed to take one person with him — at least, that’s the number of friends The Today Show offered to fly out. Drake chose Gustafson. The former was creative and spontaneous. The latter was practical and prudent. Both were just crazy enough to “chase the dragon,” as Gustafson puts it. In January 2014, after two months of successful local events and YouTube tutorials, the pair officially incorporated: Dancakes, a professional pancake art business, was born.

The next eight years would see Drake and Gustafson traverse the globe together. Dancakes took them everywhere including Louisville, Kentucky; Monterey, California; Dubai in the United Arab Emirates; and Hong Kong. Their work was featured on hundreds of companies’ social media platforms, including Disney and Dungeons and Dragons. They flipped pancakes with Steve Harvey and Katy Perry. The two became inseparable, partly because they had only each other for company as they bounced around from gig to gig. But their professional relationship would have been impossible if it weren’t for the genuine friendship on which it was founded.

That’s the story of how in September of 2018, Gustafson and Drake found themselves in Singapore, making pancakes for schoolchildren in a supermall.

As for how they found themselves playing Anthromancer in that cafe? That one’s a bit more complicated.

COURTESY DANIEL DRAKE

The motto of Dancakes is “mistakes are delicious.” For much of his life, it’s been Drake’s motto as well.

At 33 years old, Drake has made peace with the fact that fitting in isn’t his speciality. As a child, he was “very ponderous” and prone to morbid thoughts.

“I remember from being a kid where, for instance, I think I was like seven, and I was standing in my bedroom looking at my bookshelf, and it occurred to me that, technically, a car could come through my room at any time and kill me,” he says.

In middle school, Drake befriended “all the smart kids,” with whom he spent his days playing video games, such as Yu-Gi-Oh! and Dungeons and Dragons. During that time, his parents went through a divorce, and custody arrangements meant he bounced around a lot — to this day, Drake has never lived in one home for more than three years.

Drake attended high school at Gateway Institute of Technology, while his friends — the ones he would do “all the nerd shit” with — went to the more prestigious Metro Academic and Classical High School. Without his band of misfits, Drake turned inward and developed a chip on his shoulder that hasn’t quite disappeared.

“On some very, very deep level, I have a crippling fear of being unloved and not having been good enough, and that leading to people wanting to push me away,” he says.

When Drake was 19, he experienced “the single most fucked up thing that’s ever happened” to him: His 16-year-old stepbrother was shot by his biological mother, who then took her own life.

Drake’s family had moved through several Christian denominations, yet none could provide a satisfying explanation of how something so devastating could happen in a world that was inherently good. Drake spiraled into what he calls “high school nihilism,” spending joyless shifts at Courtesy contemplating life and death.

“At that time, I was still laying on my floor after my shifts looking up at my ceiling, dreading the void,” he recalls. “I think there’s a phase where the oncoming inevitability of your own death, like, fucks with you for a minute, you know?”

Drake seriously considered getting “nihilism” tattooed on his forearm, but his friends talked him out of it. Instead, a year and a half after his stepbrother’s death, he and those same friends did ecstasy together. They piled into his ex’s bathtub while new-age German band Enigma blared in the background, and Drake had a realization: He could imbue a meaningless universe with its own significance.

“What if I used the pain it made me feel to inspire me to live a more authentic life?” Drake asks. “What’s the worst that’ll happen?”

Since that epiphany, Drake’s been on a quest to be authentically himself and make money doing it.

The biggest obstacle? He can be a complex, and often difficult, pill to swallow.

For starters, he is a staunch advocate of cryptocurrency, which he views as the most viable route to legitimate systemic change. He’s also a self-identified Christian Anarchist, the ethos of which can best be summarized as “no kings but the King of Kings.” Finally, Drake is polyamorous — he finds monogamy too limiting.

Drake is so fringe that he’s even on the fringe of esoteric groups.

For instance, cryptocurrency, particularly bitcoin, has developed a reputation on par with that of the “tech bros” of Silicon Valley. Drake has found a home in the ethereum community, which he describes as full of “weird occultist people” like him, but strangers jump to the conclusion that he’s another “entitled-ass white man” salivating over the next get-rich-quick scheme.

“I’m gonna come across as an asshole to certain people regardless of what I do because I’m loud, because I’m not going to be quiet and small, because there are people who think I should be, because they see me, as a white man, as somehow responsible for everything bad that’s ever been done in capitalism,” he says.

He also concedes that part of him may simply crave controversy.

“There is a strengthening of the ego that takes place when you are certain of your correctness about something and you have the strength of character to not care if people malign you, or if you get canceled or whatever,” he says. “There’s definitely a spiritual satisfaction.”

“Spiritual satisfaction” is something Drake has been in search of his whole life. The advent of Dancakes momentarily threw him off course. However, he resumed his quest in 2015, when he was flown out to So Paulo, Brazil, to appear on a national talk show called Hoje em Dia. Gustafson stayed behind. It was the first time Drake had ever gone out of the country by himself.

“They just had me down there for a week doing pancake art for folks, and the last day was super high pressure, in the studio live with a bunch of soap opera stars I’d never heard of,” he says. “It was very surreal — I had a translator.”

The show was a success, and Drake boarded the plane home high on his own sense of accomplishment. He had seven hours in the air to fill and took to flipping through the idea notebook he carried at all times. As he did so, he stirred up the impulse he had as a kid to make his own deck of cards. Then, he had the thought that would change his life, again: Why didn’t he?

That thought became Anthromancer.

“I was feeling very empowered,” he recalls. “I credit that state of mind — that, coupled with the seven-hour flight where I was just kind of bored.”

Drake deplaned and began toying around with paper cutouts of square cards.

“Over the course of the next seven years, that idea just layered and layered and layered,” he says. “I was making these decisions along the way that kind of put me down a spiritual path — like I wasn’t expecting this at all.”

So what does this all have to do with pancakes?

The answer is not much. Which speaks to why, in May of 2022, Drake left Dancakes.

His departure was hard. Especially because it also meant a departure from Gustafson.

BRADEN MCMAKIN

Drake and Gustafson hit the ground running when they incorporated Dancakes in 2014, and they didn’t stop for the next six years. In Drake, Gustafson found a dreamer who whisked him from Kingshighway Boulevard to Katy Perry’s kitchen and beyond. In Gustafson, Drake found someone with the business acumen to make those dreams a reality.

“For the first six years of it, it was gold,” Gustafson says.

Neither had intended to make a name for themselves selling pancakes. But the internet had spoken, and the money was good.

“It’s not like we sat there in 2014 and said, ‘Let’s create this.’ It was literally through virality that this became a thing,” Gustafson says. “An article would blow up, and people would reach out and we’d do those events, and then someone would see us with those, so it was just a snowball effect.”

For Gustafson, Dancakes marked an exciting departure from his previous job in construction, though he did occasionally miss working with his hands. Drake saw the company’s success and his subsequent rise to pancake fame as a considerably more mixed blessing.

“Courtesy Diner was my frickin’ three-days-a-week day job that I did just to barely pay for my bills, so I could focus all of my other energy on what I really wanted, which was to create a career and be taken seriously for my artistic expression,” Drake says. “Then pancake art comes along, and it makes me go viral, and I get on TV and suddenly there’s this more viable path to economic well-being, and I feel like I’d be stupid not to do it.”

By 2017, two additional artists had joined Dancakes full-time, marking a new chapter in the company’s development. Dancakes had far surpassed its status as a serendipitous windfall of his former side job — yet, it was still just pancakes.

“There was definitely a sense of, ‘Shit man, the universe is just punkin’ me.’ Here I am now doing large amounts of low-effort commissions that people eat or throw away right away, and they’re based on what people want, and nobody’s really interested in what I have to say,” Drake says. “When you go to a museum, you’re looking at artists paint[ing] from their souls. It’s really frustrating when that’s what you want, and the universe is like, ‘No, no, no, no, no. You’re gonna be a breakfast jester, and you’re gonna like it. And if you don’t like it, people are gonna resent you for looking a gift horse in the mouth.'”

Drake became less interested in Dancakes and its members. Artists on the road with him would return and note to Gustafson that he’d been checked out, his mind on music, Anthromancer or somewhere else completely. Even as Drake tired of his work, patrons continued to request him specifically, compounding his pancake art fatigue — and the other artists’ fatigue with him.

All the while, Drake delved deeper into the realms of cryptocurrency, Eastern philosophy and Anthromancer.

“There was a mood shift in Dan after he became interested in this stuff,” Gustafson says. “His jovialness kind of went away.”

Whatever momentum Drake still had came crashing to a halt, along with the rest of the world’s activities, with the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. Dancakes’ primary source of income was live events, and with the world on lockdown, the artists found themselves static for the first time in years.

“[Dan] fell in love with this board game, the music behind it, all this stuff,” Gustafson says. “All these things we had to throw aside when Dancakes became a thing because we were chasing the money, chasing the fame … [We] finally got to reflect on the last seven years.”

Although Dancakes found inventive ways to sustain itself through the pandemic, the team remained largely unemployed. Drake grew increasingly restless with what he saw as his partners’ lack of vision — a gripe he maintained well after live events trickled back.

“We were never really making any big moves,” Drake says. “We weren’t like, ‘OK, what’s the big vision?'”

Meanwhile, Gustafson became frustrated with Drake’s focus on the board game and similar efforts.

“At the end of the day, when you’re Nike, people know you for shoes,” Gustafson says. “People know us for making pancakes live in front of them. That’s what will always work.”

But Drake says his primary concern wasn’t with what “will always work” — he “would rather be a messy bitch on Dancakes social media than be reined in all the time.

“What’s the worst that could happen? The business dies? So what? Wouldn’t it be more interesting to see if it doesn’t?” Drake adds.

Around this time, he was also grappling with challenges in his personal life. Drake and his second wife, to whom he was married for nearly two years, divorced.

“That kind of stuff can wear on you,” Gustafson says.

Drake’s mental health continued to slide, and so did his relationship with his coworkers. In January 2022, Gustafson and the five other artists who comprised Dancakes at that point decided to confront Drake, intervention-style. They gave him an ultimatum: Either go to therapy or lose his power to make executive decisions within the business. He went to therapy.

“I ended up playing along,” Drake says. “I was like, OK, well, maybe I have been really fucked up and shitty, you know? Maybe I’ve been a bad guy.”

When he helped stage the intervention, Gustafson meant only the best for what he saw as a friend struggling with his mental health. As the “mom” of the group and someone who had himself grappled with mental illness in the past, he wanted Drake to seek the help he needed.

“We came into that meeting not even as coworkers [but] as friends,” Gustafson says. “He needed to talk to someone about it, and it wasn’t us because we tried. I sat there and I’m like, ‘We’re not trying to make this an attack at all, but we need to get down to the root of what’s going on.'”

Although Drake committed to therapy for 12 weeks, Gustafson never felt sure that Drake truly agreed there was a need for it.

“It was basically like a I’ll-just-do-this-to-humor-you kind of thing,” Gustafson says. “It didn’t seem like he was taking it seriously.”

Perhaps that’s because Drake saw his coworkers’ confrontation more as an act of betrayal than an act of love.

“It really fucked with me for a minute,” Drake says. “I realized that they were sort of coming together and wielding power against me, and that’s something I’ve never done to them.”