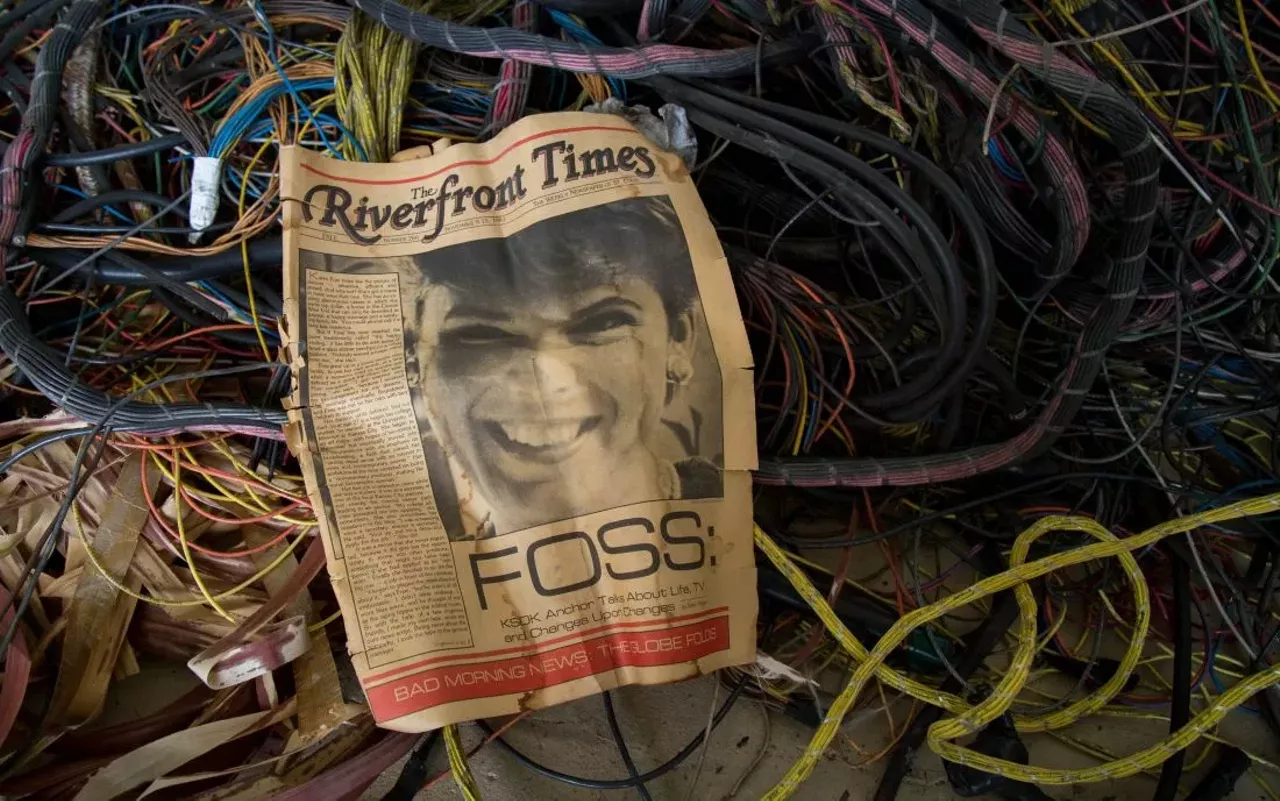

Photo by Danny Wicentowski

By reputation, the St. Louis Workhouse is a mold-infested pit whose 700-plus detainees — nearly all of whom are merely awaiting trial — are drawn from the ranks of the poor, addicted, homeless and mentally ill. Inmates, lawyers and anti-incarceration activists have alleged that medical care is withheld for months and that guards dole out beatings and pit prisoners against each other in “gladiator-style combat.” In the summer, the cells broil with triple-digit heat, although temporary air-conditioning units installed last month may finally address that problem.

On Friday, RFT accompanied 15th Ward alderwoman Megan Green on an unannounced visit to the Workhouse. Green also invited a reporter from the St. Louis American and two activists from Decarcerate STL. We did not disclose our identities as media. Green introduced us as graduate students in social work studying the effects of mass incarceration.

The tour lasted nearly three hours, and while the physical conditions appeared better than the sweating hellhole described by activists earlier this month, some horror stories appeared all too real. Among dirt and grime, detainees attempted again and again to get our attention. In some cases, they wanted to detail the bad conditions they face.

In others, they simply wanted to remind us who they are, and why they are being held — in many cases, for the smallest of offenses, and simply because they don’t have money for bail, condemning them to city custody while they’re waiting for their day in court.

The letters above the brick and glass entrance spell out “Medium Security Institution,” but everyone knows the squat, barbed-wire compound sprawled on the north riverfront as the City Workhouse.

There is irony in the nickname — it comes from an 1848 city ordinance that stipulated that prisoners who could not pay their fines would be committed to the “Work House” to pay off their debts, and then released. These days, many men and women in the Workhouse find themselves imprisoned because they cannot pay their bonds or traffic tickets. (Those accused of more serious crimes are typically held in the Justice Center downtown.) Although prisoners work in the jail kitchen or on cleanup crews, their meager pay cannot be used to satisfy their debts to the criminal justice system. And so they remain in the Workhouse, for months or even years, waiting for the wheels of justice to turn.

After introducing ourselves as social work students, we leave our phones with the security station and pass through a heavy metal door into the visitation area. A lieutenant leads us through a wide hallway that smells of bleach, and a sign directs us to the “Resident Visiting Cages.” Here, prisoners in yellow uniforms speak to their families using telephone receivers and interact behind thick panes of glass.

Our tour guide is a supervisor who started patrolling the Workhouse more than two decades ago, and despite her soft-spoken delivery and diminutive stature, she seems to command immediate respect from the inmates and guards we pass along the way. She notes that previous overcrowding had forced jail staff to place inmates on bunk beds in the gym. “We had a lot of prisoners here because they couldn’t afford their $100 traffic tickets,” she says. These days, several dorm and dayroom areas are empty and undergoing renovation.

We come to a security office. Here, a flat-screen TV monitor on the wall shows sixteen camera views of various dorm rooms and sleeping quarters.

Inevitably, talk turns to air conditioning. Last month, as a heat wave baked the city with temperatures as high as 107, protesters staged demonstrations at the Workhouse’s front gates, facing pepper spray and arrest as they demanded relief for the people inside the jail. In response to the outcry, Mayor Lyda Krewson arranged for temporary A/C units to be installed. Soon after, older sections of the jail, including the men’s daytime living quarters, were outfitted with what our tour guide refers to as “worms” — heavy white tubes running from outdoor cooling units and attached to windows.

Photo by Danny Wicentowski

It wasn’t just the prisoners who were relieved by the newly cooled-down areas. Guards and jail staff were just as happy. Yet it only took days for the jail to experience the flip side. As another supervisor tells us, some areas of the jail “were like icicles.” Staffers started showing up to work with jackets. Inmates complained as well; one tried to use a broom handle to damage a vent to stop the flow of cold air.

Green inquires about the number of inmates serving time on possession charges, and she presses for information about those who cannot afford to pay bonds. Gesturing at the “social work students,” she says we’re studying how the bail system effectively fills prisons with poor people.

It’s true, responds the second supervisor. It’s not just drug possession. Some inmates are locked up for failing to pay child support — Missouri law considers it a felony to fall behind on payments by $5,000 — and Green stops her short.

“For child support?” repeats the alderwoman, incredulous. “How does that help? If you can’t pay child support, you certainly can’t pay your child support when you’re locked up.”

But while the logic is baffling, the law is clear-cut. As our tour guide leads us away from the security office, Green notes, with resignation, that changing the criminal statute would take action in the state legislature.

The next two hours find us walking into various pods, dormitories and living spaces. It quickly becomes clear that detainees are desperate to get our attention, to share their complaints. They try both shouting and murmured messages. One woman hisses for attention, then whispers, “This place is hell.” As we depart the women’s pod to make way for dinnertime — the menu tonight is grilled cheese, beans, corn bread and chips — a female prisoner motions at the showers and tells us to watch out for fleas.

We’re led to a pod labeled “close observation,” one of three special pods reserved for male detainees who can’t be housed with the general population. The inmates here might suffer from mental illness or depression or require protective custody. A different pod houses those on suicide watch.

The “pods” don’t look like a normal cell block. The two-tiered rooms are ringed with heavy metal doors with small windows. Faces are pressed against the glass.

Our tour guide takes us to one such cell, on the first floor, and chats with the man inside. He’s left a note stuck to the window, reading, “No rec for 3 days, want to talk to supervisor.”

The men on the second floor begin raising bedlam, shouting about mold and roaches and rat bites. One yells, “Don’t listen to the shit they slinging! Shit’s fucked up here!”

“Gentlemen, behave,” retorts a nearby guard.

Our tour guide estimates that around fifteen percent of inmates require some form of observation or special care. She’s seen suicidal prisoners run up the pod stairwell and leap from the second floor. Working as a correctional officer, she says, takes a sense of duty to impart “care, custody and control” of those in custody.

Dinner is not being served in the cafeteria today (too few staff, apparently), and so we are led to the “dayroom” area, where prisoners might be watching TV or just passing the time. Our presence sends dozens of inmates to the windows to gawk at the visitors.

Turning a corner, we come face to face with a guard dangling a grilled cheese sandwich in a gloved hand. On a bench sits a detainee with long braids. He’s scowling up at the guard and the sandwich.

The guard, a well-built middle-aged man, grins at our tour guide. “He took this off a tray — shoplifting!” he says. The guard repeats the charge several times in a singsong, mocking voice. “Shoplifting! Shoplifting!”

As we head to a flight of stairs to the second floor, a prisoner shouts at us, “This isn’t a place for human beings.”

On the second-floor dorm rooms, we pass through one of the living quarters that’s been upgraded with A/C. Newspaper lines the bed frames beneath mattresses, and prisoners keep what few personal belongings they have — a Bible, a Koran, a bottle of soda, a small radio, a sheaf of hand-written notes — piled on the bed or beneath the small cots.

Back on the first floor, we stop in a room full of kitchen workers wearing white uniforms, gloves and head coverings. One man has been here two months on a weapons charge, another ten months. Neither can pay his bond. They’re relative newcomers, and they say that inmates have been known to live here – uncharged and awaiting trial – for more than two years.

Amid the crosstalk of inmates’ tales of mold and asbestos, a man with short braids and a clear, impassioned voice quiets the others. He declares that the living conditions will change “when we change ourselves.” He’s jeered and laughed at. “Come on, man,” his peers tell him. He laughs along with them and doesn’t bring it up again. I ask the man about the black mold. “It’s where we live, it’s in our dorm,” he says.

As we leave the kitchen workers and make our way back to the entrance, prisoners again crowd the bars and windows separating them from the hallway. Some shout out their sentences. “I’ve been here sixteen months on marijuana,” one says. Another: “I’ve got two kids and a cousin at home.”

Despite the repeated claims about black mold and rats, I spot only a few cockroaches in the hallway, though the building, which was built in 1966, is clearly showing its age. Waste and dirt are everywhere. At one point, I see a half-dozen black trash bags lean against a wall, right beneath a paper sign stating: “Please do not pile trash bags in the hallway.”

Photo by Danny Wicentowski

Outside the Workhouse, I ask Green what she took away from the tour. She’d last visited the Workhouse in October 2016. Aside from the newly-installed A/C, she remarks that conditions seem largely unchanged.

“When we’re talking about people who are picked up on substance abuse charges, possession charges, and then assigned a $10,000 bond and have to put up ten percent to get out, that’s an extraordinary amount of money,” she says. “It’s an extraordinary amount of strain on our system.”

It’s difficult to convey a broken system that most people never get to see up close. The Workhouse rarely grants tours to media. Green says that recent news coverage of the facility during the heat wave convinced her to arrange the undercover trip.

“I think it’s important that people who are writing about it, experience it as well,” she says. “So you’re writing from a place of knowledge and not from a place of assumption.” Green concedes that “some people in political power are not going to be happy with me” for sneaking reporters into the jail.

But Green also believes that city leaders, particularly the Circuit Attorney’s Office, need to look at reducing bail amounts and reducing the inmate population — a goal also shared by St. Louis mayor Lyda Krewson. People with addictions or mental health issues would be better served by treatment, not jail, Green says. If the city or state deployed resources to provide that treatment, we might not even need places like the Workhouse anymore.

“The cycle just keeps going,” Green says, noting that addicts and the mentally ill are frequently re-arrested, shuffled to emergency rooms and then placed back in the Workhouse. “At some point in time we have to say that it’s not working.”

At the same time, Green offers praise for the jail staff, especially the supervisors she encountered during the Friday tour.

“Their budgets are continually getting cut, both from the city and the state level, and services that were there ten or fifteen years ago just aren’t available anymore,” Green says. “They’re having to get creative in how they’re able to address the mental health issues and substance abuse issues in there.”

Green shares a similar goal with anti-incarceration activists and St. Louis Treasurer Tisharua Jones: What the Workhouse really needs, she argues, isn’t expensive upgrades or renovation. It needs to be shut down.

Green later explains that she’s planning to float a counter-proposal to the bill already proposed in the Board of Aldermen that would place a half-cent sales-tax hike on the November ballot. Green says her proposal would also create a tax hike, but this one would hit business owners with a payroll tax instead of residents. She claims it would raise $10 million more than the current bill.

“These funds will transition the Workhouse into a rehabilitation center that helps to end the cycles of mental illness, addition and poverty that keep people coming back to the criminal justice system,” Green writes in an email.

Transforming the Workhouse from its current position as a jail (and a mental hospital of last resort) would take sweeping cooperation between city agencies, and likely the state as well. But if it works, suggests Green, the Workhouse would become unnecessary. On that day, with the population of inmates decreased, the Workhouses’ services would “no longer be needed.”

And then, Green writes, “the aging facility can be closed for good.”

Follow Danny Wicentowski on Twitter at @D_Towski. E-mail the author at [email protected]